India, Jewel in the Cartier Crown

BOOKMARK

A family celebration, a bottle of champagne and a trunk of letters lying forgotten in a cellar led to a trail that has chronicled the story of the House of Cartier, the uber-luxury international jewellery brand. While the story was scripted across four generations that grew the family business into a global empire, the tale was a great, great, great-granddaughter’s to tell.

Francesca Cartier Brickell’s recently published The Cartiers: The Untold Story of the Family Behind the Jewellery Empire (Penguin/Random House – 2019) offers a riveting and substantial account of the Cartier dynasty’s storied saga. The sixth-generation descendant of the famed family, Cartier Brickell returns to the man who founded it all, Louis-François, who inherited a jewellery business from his master in 1847 and gave it his name. She follows the trail from his modest Parisian store, to the Cartier men and women who developed the business into the preeminent jewellery establishment for the world’s elite.

The book focuses on Louis-François’s three entrepreneurial grandsons, who went on to take the firm forward on the world stage. King Edward VII of Great Britain referred to Cartier as "the jeweller of kings and the king of jewellers”. With the three savvy Cartier brothers at the helm of the growing empire, clients included the world’s cognoscenti: the British royal family, Russian Tsars, American heiresses, Hollywood filmstars, and chief among Cartier’s loyal and esteemed clientele were Indian Maharajas.

These Indian rulers were among the jeweller’s top-tier patrons, the best-known in this circle being members of the royal families of Patiala, Nawanagar, Kapurthala and Baroda. It was Cartier Brickell’s great-grandfather Jacques who was the driving force behind the renowned commissions placed by these Indian princes and the book is full of the backstories and encounters through his eyes.

He played a pivotal role in the firm’s entry into India and the country would remain a key market for Cartier for the greater part of the early 20th century. In fact, Jacques was so buoyant about India that after his visit in 1911 and upon his return to Europe, he organized an exhibition titled ‘Oriental Jewels and Objets d’Art Recently Collected in India’.

Held in the spring of 1912 at Cartier’s London branch, the exhibition showcased the exquisite treasures he brought back from his travels and it was a “resounding success”, giving the public a taste for Indian design while also firmly establishing Cartier’s foothold in the subcontinent and linking the firm with India and the East.

Also owing to his deep appreciation for aesthetics and culture, India left a prominent impression on Cartier’s design legacy throughout the 1920s and 1930s, coinciding with a time when Europe’s fascination with the ‘exotic’ influences of India and the Orient reached a pinnacle. Cartier’s ‘Indian style’ saw an infusion of carved gemstones, multi-coloured settings, paisley motifs, shoulder tassel brooches – even the sarpech – which were all integrated as mainstay designs in a profusion of remarkable pieces created by the firm during this period. The importance of the Indian legacy on the esteemed outfit’s global evolution cannot be overestimated.

Cartier Brickell was recently in India and in between speaking engagements, she ventured to Kapurthala, following the footsteps of Jacques Cartier, who had visited there a century ago. LHI had the privilege of speaking with her there, about the extraordinary Cartier-India connection.

I am super excited to read this book. Congratulations and thank you for sharing this epic account of your family’s history. Can you tell us briefly what first compelled you to chronicle the story of the House of Cartier?

I grew up hearing anecdotes from my grandfather (Jean-Jacques Cartier, who was the last of the family to manage a branch of the firm). He ran the London branch until he retired in the 1970s and the business was sold at that point. I came along a few years later, and I always loved listening to his stories. As I became older, I entertained the idea of writing them down to preserve them for future generations but it wasn't really a bigger idea than that.

Then, on his 90th birthday about 10 years ago, I was looking for a bottle of champagne in the cellar of his house in the South of France. I was about to give up looking when I spotted a trunk in a dark corner of the cellar, and went over to it thinking maybe the champagne was inside. When I moved some wine bottles and other objects off the top of the trunk, I found it was covered in old travel stickers. By now, I didn't really think the champagne was inside but I wanted to know what was, so I opened the trunk.

There, just waiting to be discovered, were hundreds of letters that – as I would find out later – basically chronicled the story of my family over four generations and the firm they founded. For me, that was the turning point. I couldn’t simply shut the case and leave those letters to gather dust for another 40 years. I felt inspired, even duty-bound, to keep the story alive.

Your great-grandfather Jacques Cartier made his pioneering inaugural visit to India in 1911, quite strategically to coincide with the great Delhi Durbar coronation of George V and Queen Mary. What compelled him to venture so far from Europe? What were some of his impressions of India?

The three Cartier brothers, Louis, Pierre and Jacques, had this dream to build the leading jewellery firm in the world. They inherited the Parisian firm which their grandfather had founded and they then came up with a plan to take it beyond Paris. They looked at a map of the world and literally divided it with a pencil: divide and conquer.

Louis took Paris, the firm’s headquarters, as he felt that was his right as the oldest brother, while Pierre, the middle brother, took the Americas and he would go on to open a branch in New York. So it fell to Jacques, the youngest brother, to take England and with that responsibility went responsibility also for clients in the British colonies, most importantly India. Jacques was also the family gemstone expert, so his trips to India were not just about selling jewels but also buying them.

Writing back home from the Durbar, Jacques explained that he had brought all the wrong jewels with him to sell! He had not realized that, in India, it would be the men choosing the jewels for themselves rather than for their women. So the delicate and feminine Belle Epoque-style necklaces and tiaras that Jacques had packed with him from Europe were entirely inappropriate. In fact, most of the orders he picked up on that trip were for the simple pocket-watches that were all the rage in Paris at the time.

So, as it turned out, the Durbar was a bit of a disappointment when it came to sales, but it did at least enable Jacques to meet many of the ruling princes in their majestic tents across the Durbar encampments. And from those initial meetings, he would receive invitations to visit them in their palaces across the country.

After the Durbar, he travelled around India, meeting various Maharajas. Sometimes he stayed in opulent palaces but at other times he was simply a travelling salesman sleeping on rough matting on the floor in basic station houses. He loved India and he wrote with absolute awe about the history, the sites, the architecture and the carvings. Sometimes, he would sketch his surroundings, at other times he would just soak it all in. He wrote that, in the ten centuries that preceded his era, it was India that reigned supreme in the artistic world.

On his first trip out to India, Jacques was given a stubborn donkey for transport and he said, “Enough! Next time, I'm coming out with my Rolls-Royce.” So, on later trips, through the 1920s and 30s, he traveled with the Rolls, his chauffeur and his personal doctor (medical care was important as he had been gassed during the First World War and had very weak lungs). He would also often travel with his wife, Nelly, a larger-than-life character who adored adventures and brought with her not only 17 suitcases of clothing but also a personal dresser to assist her.

So there they were, a merry group of five from the verdant hills of Surrey in England, taking a three-week boat voyage all the way from Marseilles to Bombay and then spending several months travelling around India while “Sahib Cartier” (as Nelly referred to her husband in letters back home) met clients and bought gems. My grandfather recalled hearing stories of how everything was possible out there: when encountering a large stream that the car couldn’t cross, a raft was simply built for the Rolls Royce. Or when they couldn’t drive over the Himalayas to meet the King of Nepal, they literally took the Rolls apart, carried it in pieces and later reassembled it. There was a can-do attitude.

Nelly wrote letters back to her children, who she missed terribly. She would fill them in on things she had seen that she knew would excite them, like the monkeys outside the train window peeling mandarins and bananas, or the elephants picking up coins in the temple with their trunks. She was a great sport and never complained, even when sleeping in very uncomfortable places. At one point, she wrote that they had arrived at Maidens Hotel in Delhi, thrilled to be in such luxury after “roughing it” in the South.

A lover of music, she even asked if a piano could be brought to her hotel suite and a few hours later, was astonished when she looked out of her window to see six men carrying it on their backs up the road. Sometimes, Jacques would go off travelling for work and she stayed back in Delhi. “Sahib Cartier is more full of business here than in London,” she wrote home.

Each part of India is so different and Jacques, who travelled all over, talked a lot about that in his letters. In some ways, it's changed so much, as has the world, but equally on my trips here I was struck by those aspects that haven't changed so much. For example, family businesses: I met one jeweller whose family has been running their business for 13 generations – and that’s not even all that unusual here.

Of all of the fascinating Indian personalities Jacques Cartier encountered, which one intrigues you most?

This is rather hard to answer because there were so many! For example in Baroda, he was enormously impressed with the progressive Gaekwad Sayajirao III and his Maharani (who he called “a superior woman”,) while in Nawanagar, he would became good friends with the cricket-playing jewel-connoisseur Maharaja Ranji of Nawanagar. He was very interested in the fact that many rulers were working hard to improve their own states, like Maharaja Jagajit Singh of Kapurthala, who established schools, introduced co-education and integrated a modern judicial system.

So whereas on one hand, Maharaja Jagajit Singh was an excellent Cartier client, on the other I have found it fascinating to learn more about him as a man: how he believed in equality, hired people based on their merits, and built places of worship for those with different faiths. For me, coming here to Kapurthala and hearing more about his work and seeing some of the truly stunning buildings he commissioned – from the incredible French-style palace to the Moorish Mosque – has really brought it all to life.

Is there a particular favorite of all the Indian commissions that were made for the Maharajas?

Jacques particularly loved emeralds and there are a few emerald creations Cartier made for the Maharajas which I mention in my book, which are truly extraordinary. For example, the Maharaja of Kapurthala's emerald turban ornament made for his 1927 golden jubilee, and an important emerald necklace for the Maharaja of Nawanagar.

These were often made of very precious, antique, carved emeralds which were remounted, and the craftsmanship that went into setting them into their new design was phenomenal. My grandfather told me that the mounter was sometimes given 48 hours of work before actually mounting an emerald in the jewel’s setting. Since they were so fragile, it was imperative that the mounter was totally calm and still. Any slight tremor of the hand could cause the emerald to crack or, if it wasn't mounted exactly as it should have been (ie. if there was just a bit too much space between the stone and the mount), it might shift around in the setting and crack at a later date.

When one understands this, I think one sees the jewels in a new light, at least I did. They are not just about the magnificence of the creations but also a testament to many ‘unsung heroes’, as my grandfather called them, the incredibly skilled designers and craftsmen behind-the-scenes working on turning dream pieces into reality.

It is probably worth adding that Jacques really loved gemstones; he had an almost spiritual connection with them and possessed a strong sense of which setting would be right for each one. Part of this was down to the gem’s history – he respected the culture from which it had come, so with those antique Indian gems, the designs he chose tended to be Indian-themed in some way.

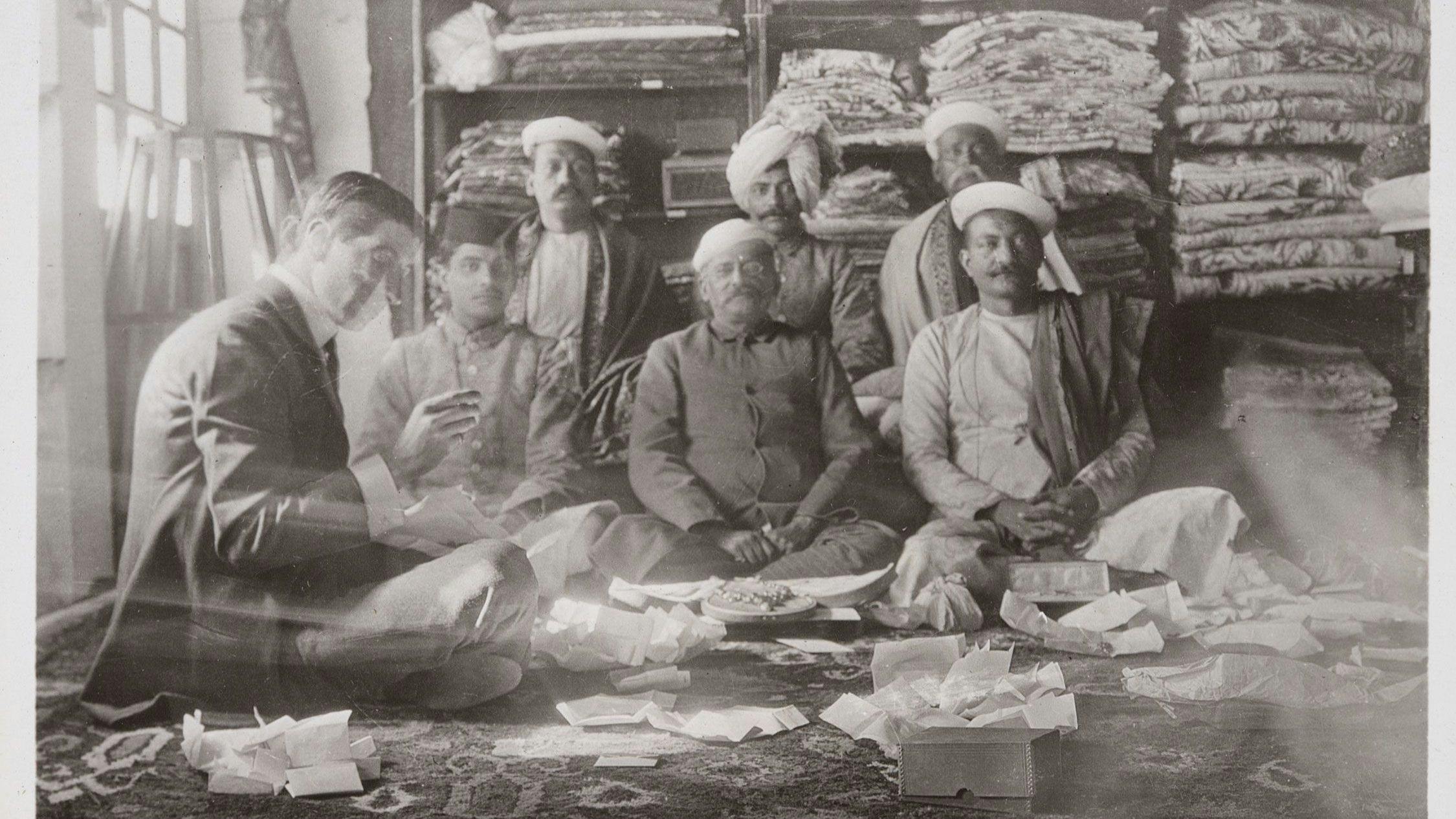

There is a famous photo of Jacques (see below) sitting cross-legged, inspecting gemstones along with some Indian gem dealers in the 1920s. I only recently discovered, with the help of a friend from Singapore, that this photo was taken in Kanjimull Jewellers’ old shop in Delhi. So I contacted the Kanjimull family on this India trip and managed to meet up with some of them. That was a fun connection to make.

Many of Cartier’s designs in the 1920s and 30s for the international market echoed Indian designs and themes. Can you give an example of how the Indian influence was manifested in Cartier’s style?

In India, Jacques said “one does not see as in the English light... It is all like an Impressionistic painting... one vivid impression of undreamed gorgeousness.” Back in Europe, after his trips out there, he would combine vivid carved rubies, emeralds and sapphires together to recreate that brilliant assault on the senses. Nowadays, it may not be so unusual to mix coloured gemstones together but it was quite daring at a time when the fashion was more monochrome and it went down very well with the trendsetters of the day such as Daisy Fellowes (an heiress to the Singer sewing machine fortune). Tutti-Frutti was a term that was only coined much later – after Jacques’s lifetime. He called his Indian-inspired creations his “Hindou jewels”.

The carved gems he used were less expensive to buy than larger precious gemstones (partly because any flaws could be carved out), so during the 1930s they became quite good “Depression-era jewels”. Nowadays, however, they have become so iconic that they often reach record prices at auctions!

The Indian Maharajas were among the most important clientele of their time for many European luxury purveyors. How important was their patronage to Cartier?

India was enormously important because, suddenly, after the devastating First World War, which coincided with the Russian Revolution, the Cartiers lost many of the big Russian Romanov clients and European royal clients who, having been some of the longest-standing and most substantial buyers of jewellery before the war, were suddenly left without anywhere near the same funds at their disposal.

So the biggest clients then came from America – the Roaring ‘20s were boom time in the US – and also from India. Then suddenly, in 1929, there was the Wall Street Crash, followed by the Great Depression and many of those American clients also dried up. As a result, through the 1930s, the Cartiers came to rely heavily on the Indian Maharajas who had remained in many cases, largely unaffected by the downturn in the West.

This was exemplified in 1931, when a necklace created from a cascade of coloured diamonds was made for the Maharaja of Nawanagar. It took quite some time to source all the diamonds to make into the necklace – years, in fact. And my grandfather told me how proud his father Jacques had been of this necklace – he called it the “realization of a connoisseur’s dream”. Commissions on that scale were simply not really happening elsewhere at that time, which is why Jacques kept travelling to India, as it was such an important market. So, in a way, the Indian patronage really helped to preserve the craftsmanship and artistry in Europe.

It must be very sentimental being in India, tracing the journey of Jacques Cartier. What has been particularly memorable for you?

It's very special to come back to the places where he went and to see them almost through his eyes because I've read his diaries and seen his sketches. I walk into the same temples and see the same carvings he sketched, visit the same palaces. You feel a jolt of connection and it brings it to life a lot more, especially when I am lucky enough to speak to the descendants of people he had known at that time. That's most moving because it's a personal link. To actually come here, see it all in colour and meet people whose forebears he met and talked about makes me feel more connected to the story.

Recently, I enjoyed meeting family members from the Royal Houses of Patiala, Baroda, Jaipur and of course right here in Kapurthala – all whom had a close relationship to my own family. So it’s like it has all come full circle and it feels right that I have written this book, keeping those links alive in some way. I look forward to many return visits to India to meet more families and others who share historic connections to the Cartiers.

Cover Photo: The Maharaja of Kapurthala wearing his Cartier turban ornament

– ABOUT AUTHOR

Cynthia Meera Frederick is the biographer of Maharaja Jagatjt Singh of Kapurthala. She lectures frequently on Punjab’s royal heritage.