Kalinga Before Ashoka (7th BCE - 3rd BCE)

BOOKMARK

There is a story that the Sri Lankans hold dear. It goes back to somewhere around the 6th BCE when a banished prince, the grandson of a princess of Kalinga (who had eloped with a lion), made his way to the island deep south with a band of 700 men. He defeated the local inhabitants the yakkhas and went on to rule Sri Lanka as King Vijaya. By now, he had taken the title of his father and grandfather (the lion) and that is how his people came to be known as the Sinhalese.

This story is mentioned in the Buddhist text Mahavamsa and the earlier Deepavamsa which chronicle the history of the people of Sri Lanka. They were both written somewhere between the 3rd and 5th CE - roughly 900 years later.

The earliest reference to Kalinga in Indian texts comes from the Puranas where Bali the king of the Anavas is said to have divided his kingdom among his five sons Anga, Vanga, Kalinga, Pundra and Sushma. The splintered kingdom came to be named after the sons. Anga’s capital was Malini close to present-day Bhagalpur and included the region of Munger. Vanga was further east corresponding to the present day Dacca and Chittagong areas, Pundra was northern Bengal, Sushma comprised of the area of Burdwan in present-day West Bengal and Kalinga - included coastal Odisha and the northern part of present-day Andhra.

The Mahabharata too mentions Kalinga. The Kaurava Prince Duryodhana’s wife Bhanumathi is said to have been a princess of Kalinga. Interestingly, there is no reference to Kalinga in the period of the 16 Mahajanapadas around 800-600 BCE.

But legends and myths aside, every person who has read Indian history would be familiar with Kalinga, the kingdom covering most of present-day Odisha - thanks to one of the most famous wars in Indian history that was fought over it - the great War of Kalinga, which we are told transformed the ambitious and cruel Mauryan Emperor Ashoka, to a pious Dhamma (Dharma) preaching beacon of peace.

But why was Kalinga such a coveted prize for Ashoka? And how did this region, on the eastern edge of peninsular India, manage to put up such a big fight?

While literary records are silent on these questions, today, thanks to decades of painstaking excavations by teams of archaeologists, across the broad expanse of ancient Kalinga, stretching in its prime from Tamralipti in present-day West Bengal, to Srikakulam in Andhra Pradesh, we are getting a clearer picture.

The Geography of Kalinga

Tucked away, with a cover of thick forests around it and a network of rivers and rivulets draining into the Bay of Bengal, the area of present-day coastal Odisha was ideal for habitation and settlement. The rich alluvial soil allowed communities to thrive and there are many sites here dating back to the early neolithic period. Further inland, the rich mineral deposits (in the North and West) helped communities take the leap as chalcolithic cultures evolved and eventually the use of iron became prolific.

While there is evidence of numerous mesolithic and neolithic sites across the state, recent archaeological excavations give us a sense of how early agricultural settlers evolved with the use of copper in the chalcolithic (copper age) period.

The evidence of chalcolithic cultures in Odisha became well known after the excavation of Golbai in coastal Odisha. It was further strengthened in 2013 when archaeologists found the remains of an adult human being who might have lived around 4,000 years ago in the Banga village near Harirajpur, around 15km from Bhubaneswar. What was interesting is that the site yielded a lot of tell-tale signs of a chalcolithic site - pottery sherds, stone artefacts, animal bones, copper fragments and living areas indicative of ancient habitation. The copper ornaments on the skeleton also indicated that the skeleton belonged to someone of local importance, probably a chieftain.

This discovery made at Banga as well as other sites showed the evolution of cultures in Odisha as It threw light on the emergence of early farming communities, their settlements and exploitation of natural resources.

Professor of Anthropology at the Utkal University Kishor Kumar Basa who was part of the team that studied the site along with Archaeologist R.K. Mohanty, from the Deccan College, believes that sites like this provide a background to the emergence of urban settlements. Besides, they indicate the continuous evolution of communities in the area. In fact, he says that many of these sites simply evolved into urban settlements and the early urbanisation of Odisha has to be looked at in context of sub-regional specificities - the rich alluvial soil of the coast, the abundance of minerals in the north and the large supply of semi-precious stones in the south. It is interesting to note that even today, areas like Mayurbhanj, Keonjhar and Sundargarh in the region, have some of the richest iron ore and copper mines in the subcontinent.

The natural resources and fertile soil of the Kalinga helped settlements prosper but what would have added fuel to growth must have been trading. To understand this, you have to head to the Chilika Lake, a brackish water lagoon stretching 64 km from the Khurda district to Ganjam district in Odisha. Connected to the Bay of Bengal through a narrow sea mouth, this lake acted as a window, connecting the region to the world - East.

The earliest habitation around the Chilka also goes deep into prehistory. Archaeologists have found neolithic sites dating back to 2300-2100 BCE and more advanced Chalcolithic sites from 2100 to 900 BCE here. Interestingly, by the early historic period there is also evidence of a clutch of ports around the lake - from Palur, referred to by the Greek geographer Ptolemy (150 CE) as Paloura and Manikapatna a port that was active all the way from the 2nd BCE. The Chelitalo port near present-day Konark was referred to by the Chinese traveller Hiuen Tsang in the 6th CE.

If this was the maritime base around the Chilka lake, further north you had the important port of Tamralipti - literally the copper port, that was the centre of trade through the early historic period and further south Kalingapatnam, perhaps the largest of all the regions ports.

The material found across South East Asia - Indonesia, Thailand, Burma and Ceylon of the famous Rouletted Ware pottery, which is also found in these Odisha ports indicate a wide network of trade contacts between Kalinga and South East Asia, Ceylon and even (perhaps indirectly) Rome. Dr Kishor Basa believes that the region of Kalinga played a crucial role in the larger Bay of Bengal trade world. It was a conduit for ideas, people and material, for centuries - long after King Vijaya set sail.

In fact till much later Kalinga was known mostly for its overseas connections. The poet Kalidasa (4th-5th CE) refers to the king of Kalinga, in his work Raghuvamsha, as Mahodadhi Pati -the lord of the Ocean and the Mahayana text Mañjuśrī-mūla-kalpa refers to the Bay of Bengal as the ‘Kalinga Sea’.

In the year 261 BCE when Ashoka decided to attack Kalinga, it would undoubtedly have been a prize catch. The region, close to Pataliputra his capital, would have been prosperous and rich in resources - essential to feed the ambitions of an empire constantly at war, and it would have also been strategic, given the string of ports it boasted of.

Excavations around the villages and cities of modern-day Odisha over the last 2 decades have also given us a sense of what the region of Kalinga was like, on the eve of Ashoka’s attack.

What Sisupalgarh Tells us

On the outskirts of Bhubaneswar, in a village which is fast turning into a suburb of the city, you will find the ruins of a much older one. Spread over an area of 1.2 km is the city of Sisupalgarh surrounded by a square fortification, with two gateways on each side. A moat filled with water ran around the fort.

Archaeologist Dr RK Mohanty who has been part of the team that excavated the area, over the last few decades says “Materials found here indicate that the earliest levels of the city go back to 7th BCE. Carbon - 14 dating indicates cultural sequences that have pushed back the antiquity of this ancient city, which was till recently thought to have been from the 3rd BCE.” Ashoka’s Dhauli edict a few km away from the site of Sisupalgarh and evidence of palaces/pillared halls from the later period (2nd BCE- 1st BCE) have led scholars like Mohanty to believe that Sisupalgarh, was a thriving city in Ashoka’s time and it might have faced the brunt of the Mauryan aggression. This area (Sisupalgarh- Dhauli) must have been where the famous Kalinga war took place. There is even a memorial in Dhauli to commemorate it.

Subsequent excavations along the coastal length of Odisha has thrown up even more.

Amazingly, Sisupalgarh which was, according to Mohanty, one of the biggest cities of its time, anywhere in the world, was actually part of a network of urban centres stretching along the east coast of Kalinga sandwiched between the Bay of Bengal and the Eastern Ghats. Stretching for about 400 km were large urban cities, interspersed with smaller satellite ones. From Radhanagar to the North East of present-day Bhubaneswar to Sisupalgarh, to Jaugada or Jaugarh and finally Dantapuri in present-day Srikakulam district of Andhra Pradesh. Between each of these cities was a smaller satellite city roughly 1/4th the size. Of the lot, Dantapuri was the largest with an 80-meter moat running around its fortification.

Mohanty shares some interesting insights on these sites “Our excavations have shown that these smaller cities were almost identical to the larger cities in the way they were planned. They too had fortifications and moats around. This network of larger cities interspersed with smaller ones, made it unique unlike any other site found in India, or perhaps even the world and showed how well planned this network was.”

Each of the sites was located close to the river and the water resources that were needed - for consumption and navigation. In Sisupalgarh, excavators have found a jetty near the Northern gateway by the moat - this probably was part of the supply network to the city that came from these waterways.

Interestingly, despite the obvious affluence of this area, there is little we know of Kalinga from ancient records. The region plays no part in the era of the sixteen Mahajanapadas around 800-600 BCE. There is also no mention or reference to a single political authority or ruler in Ashoka’s edict where he talks of the Kalinga war. This has led historians and experts to surmise that the Kalinga region may have been led by a confederation of tribal chiefs or an oligarchy. Given that there were so many large cities co-existing, there must also have been relative peace and stability before Ashoka’s attack.

The Kalinga War

Close to Sisupalgarh is the site of Dhauli, on a hill where the famous Kalinga Battle is said to have taken place. It is said that so fierce was the battle and so bloody its outcome that the river Daya, which Dhauli overlooks, had turned red with the blood of the dead, on the fateful day of the Kalinga war. The destruction was so complete that Ashoka famously had a change of heart and path.

Interestingly while there is a major Ashoka rock edict at Dhauli and also in the site of Jaugada close by, neither of them refer to the bloody and significant Kalinga war. In Dhauli, Ashoka instead stresses the importance of the rule of law.

To feel his heartfelt remorse for what happened in Kalinga, you have to head to Kandahar, thousands of miles away.

Here, in Ashoka’s rock edict XIII, the Mauryan Emperor comes clean. He writes:

“Beloved-of-the-Gods, King Piyadasi (as Ashoka was referred to), conquered the Kalingas eight years after his coronation. One hundred and fifty thousand were deported, one hundred thousand were killed and many more died (from other causes). After the Kalingas had been conquered, Beloved-of-the-Gods came to feel a strong inclination towards the Dhamma, a love for the Dhamma and for instruction in Dhamma. Now Beloved-of-the-Gods feels deep remorse for having conquered the Kalingas.

Indeed, Beloved-of-the-Gods is deeply pained by the killing, dying and deportation that take place when an unconquered country is conquered… the killing, death or deportation of a hundredth, or even a thousandth part of those who died during the conquest of Kalinga now pains Beloved-of-the-Gods. Now Beloved-of-the-Gods thinks that even those who do wrong should be forgiven where forgiveness is possible.”

After the conquest of Kalinga, while Ashoka is said to have turned to Dhamma and the spiritual path, the Mauryan state administration continued with the task of governance. Records show that Kalinga was divided into 2 parts - the northern half was headquartered in Tosali (modern Dhauli) and the other probably at Samapa the old name for Jaugada.

Much later in the 1st CE the Roman author Pliny the Elder mentions Kalinga. He writes “The tribes called the Calingae are nearest to the sea and the royal city of Calingae is called Parthalis ( probably Tosali).”

After the decline of the Mauryan empire, the next time Kalinga blazes back into the history books is during the reign of the Chedi king Kharavela. While his dates are foggy - anywhere between the 2nd BCE and 1st BCE, there is a lot we know of the king.

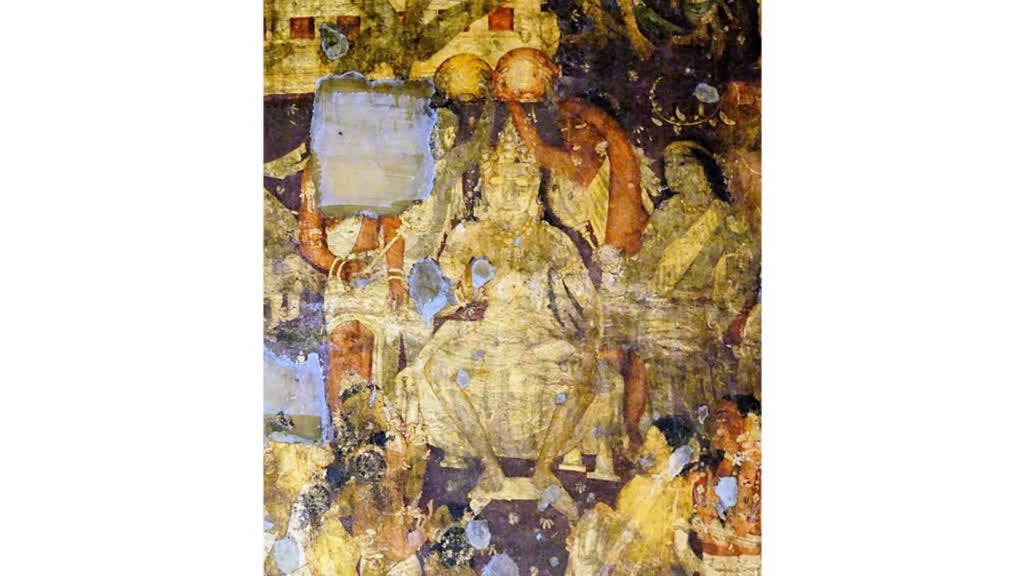

Close to Bhubaneswar are a complex of Jain caves at Udayagiri and Khandagiri. At the entrance of the first, in a large cave aptly called the Hathigumpha (it can fit an elephant), you will find an inscription that details this chapter of Kalinga’s history. It tells of the exploits of King Kharavela and how he ‘avenged’ the slight meted out to the people of Kalinga by the Nandas and the Mauryas, a few centuries earlier.

According to the inscription - Kharavela ascended the throne of Kalinga when he was 24. He went on to make a mark - marching on the path of ‘Vijaya’ conquering territories and defeating kings in Berar, Rajgriha and Masulipatnam - near present-day Chennai. He is even said to have defeated the Pandyas, in the deep south.

Most significantly, the Hathigumpha inscription adds, during his exploits, Kharavela marched on Magadha to bring back important Jain images that the Nandas had once taken away from Kalinga, thus restoring the ‘pride’ of Kalinga. These were most probably housed in Sisupalgarh, which archaeologists like Mohanty believe was also his capital.

Though Kharavela’s conquests are marked, his successors did little to add to his glory and after he passed on the kingdom of Kalinga fragmented to smaller pieces. But, it is telling that a king a century or two later, would refer to the great affront Kalinga faced. It also indicates just how vibrant and prosperous this region would have been, to bounce back and shed the yoke of empire as soon as the Maurya Empire fell.

Sadly, we still know little about the early historic period of Kalinga and how it became a base for the spread of men and ideas over the next few centuries. Many sites are waiting to be excavated.

For now, all that we can do is piece the story of Kalinga together, bit by bit.

Excavation photos courtesy: Report on Sisupalgarh by BB Lal, RK Mohanty and Monica Smith

This article is part of our series ‘Two Thousand Years of India’s History’, where we focus on the period between 600 BCE- 1400 CE, and bring alive the many interesting events, ideas, people and pivots that shaped us and the Indian subcontinent. Dipping into a vast array of material - archaeological data, historical research and contemporary literary records, we seek to understand the many layers that make us.

This series is brought to you with the support of Mr K K Nohria, former Chairman of Crompton Greaves, who shares our passion for history and joins us on our quest to understand India and how the subcontinent evolved, in the context of a changing world.