The Exhibition of 1851 & the Jewel in the Crown

BOOKMARK

Why is the Koh-i-Noor diamond one of the most famous diamonds in the world? How did the Victoria & Albert Museum come into being? How did British factories get a hang of how exotic Indian textiles were made? These varied events, have one thing in common - The Great Exhibition that was hosted in London in 1851. It dazzled the thousands who came to see it, from the commoner on the street, to the Queen of the British Empire. It also left a lasting image of ‘exotic’ India.

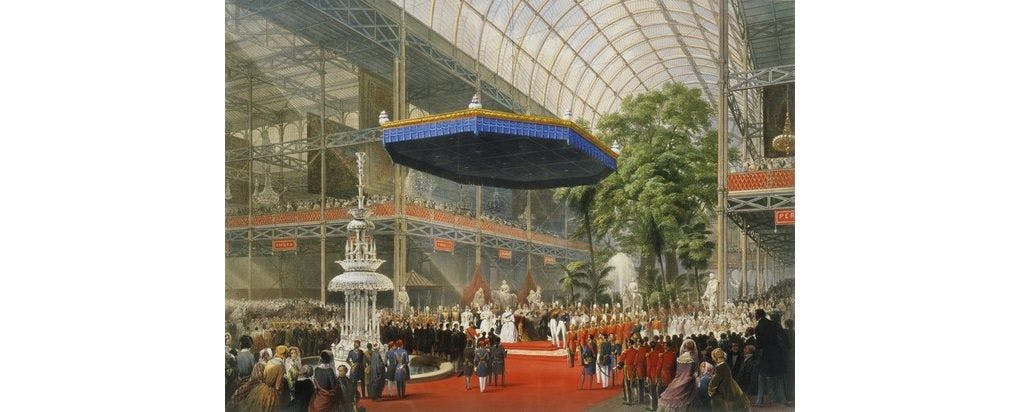

The Great Exhibition was put up to highlight ‘the Works of Industry of All Nations’. A spectacular ‘Crystal Palace’ was created at Hyde Park in central London. This was a glass structure with massive chandeliers and exhibits of 28 countries - including many areas where Britain was increasingly getting involved in or had relations with. Also present were countries like France, the United States and Canada.

The added attraction of the exhibition, was that it was sponsored by Queen Victoria and Prince Albert through the Society of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce. Prince Albert was personally involved and it was intended as a coming together of the manufacturing and design innovations from the world.

The 1800s had been a time of great change in England, driven by events both at home and abroad. The Industrial Revolution, the steam engine, the expansion of its overseas territories... the list was long and the exhibition seemed a good opportunity to showcase Britain's success, especially since Paris had held spectacular exhibitions like this between 1798 and 1848.

Not to be outdone, London put up quite a show. The city’s central Hyde Park was transformed. A massive building made of glass, iron and wood, spread over 19 acres was created. It was called the Crystal Palace or the Great Shalimar and it was a technical marvel. Built by horticulturalist Joseph Paxton it took its inspiration from the design of a greenhouse.

The Exhibition also had a clear message. It presented the beginnings of a ‘New World Order ‘, with Britain at its centre and India as its crown jewel. Many of the ideas and associations about India, which became part of everyday discourse, had their beginnings here - be it the image of an ‘exotic’ India, the land of unbelievably rich Maharajas, opulent fabrics and great jewels.

Interestingly, the exhibition didn't start off as show of might of the British Empire but actually came from the organisers being dismayed by the lagging state of British industrial design. While technologically Britain had advanced by leaps and bounds in the decades leading to the exhibition, it stood nowhere with regards to design. Thus, the organisers wanted to bring the best designs from around the world to the country so that British manufacturers and designers could learn from them and innovate. Of course, it ended up accomplishing far more and created in Britain a regard of its might, unsurpassed till date.

At the exhibition many sovereign countries had their own pavilions, but India was not extended the same courtesy since it was seen as a dependent of the British. The planning and execution of the displays of India was completely in the hands of the East India Company.

India was the trophy and England the victor, something which was on full display at the exhibition. A central position was given to many Indian exhibits, from a stuffed elephant covered in rich fabrics and royal regalia to the Koh-i-Noor diamond, recently confiscated from the 11-year-old deposed Maharaja of Punjab, Dileep Singh.

India was given 30,000 sq ft of exhibition space, while the second largest colonial display, that of Canada only had 4000 sq ft. Even the USA which had been allotted 40,000 sq ft only utilised 12,800 sq ft!

The Indian exhibits had been assembled by John Forbes Royle, who was born in India in 1799 and had served as the Superintendent of the Botanical Gardens in India for the Company.

Goods were curated and sent to the exhibition from the different provinces of British India like the Bombay and Bengal Presidencies. During the collection of the objects, a need was felt for local museums of art and design to be built. In fact, the replicas of the exhibits sent for the Great Exhibition formed the nucleus of the City Museum of Bombay - now known as the Bhau Daji Lad Museum.

Amongst the exhibits on display was the ivory throne gifted by the Raja of Travancore . In fact it was perched on this, that Prince Albert closed the exhibition. There were Indian fabrics of all kinds - woven, embroidered, embellished, decorative objects, jewellery, pottery, carpets and even boats and fishing nets. Particularly fascinating were the displays of raw materials like ivory, horns, bones, shellac, metals and the tools used to work these materials. These not only awed the visitors but also provided local manufacturers handy guides to be able to replicate these handcrafted Indian goods cheaply through the factories in England.

Surprisingly enough, despite the British penchant for the same, not many ancient or historic artefacts from India were a part of the exhibition. It was the contemporary arts and crafts and raw materials from India which took centre-stage. This was in keeping with the general theme of the exhibition of ‘Arts and Industry’.

By the time the exhibition came to an end on the 15th of October, 1851 (it went on for five and a half months) 6 million people, the equivalent of one-third of Britain’s population had visited it. Not only did these people include common folk, but also some of the leading lights in art, culture, science and literature like Charles Dickens, Charles Darwin, William Thackeray, Samuel Colt and Lord Alfred Tennyson.

At the end of the exhibition Prince Albert felt the need to keep the momentum going and suggested the creation of a ‘District of Museums and Colleges’ for the study of arts and sciences in order to promote British manufacturing. This gave birth to the South Kensington School of Art, as well as the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. Meanwhile, it was a visit to the exhibition, that inspired Lockwood Kipling the father of Rudyard Kipling to pursue a career in the arts and design. Even Sir Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy decided to establish the Sir JJ School of Arts in the city of Mumbai - after seeing the exhibition.

The Mapping of Indian Textiles

The Great Exhibition may be a distant memory, but it did leave quite a legacy. It inspired Britain to be even more aggressive in its ambitions, it shaped the way India came to be seen and it left behind some lasting institutions.