Age of Literature: The Art & Science of Living (6th BCE - 1st BCE)

BOOKMARK

You’ve probably read the following sentence many times: “The enemy of my enemy is my friend.” Truisms like this become clichés that acquire a life of their own and are passed on through the ages, without us ever really pausing to wonder at their origin.

So, if you don’t know who penned the truism above, we’ll tell you. It is attributed to the famous political strategist and thinker, Chanakya or Kautilya, in the Arthashastra, back in the 4th century BCE. Even more amazing is the fact that Kautilya’s timeless treatise on statecraft was just one of the many great works that set the stage for entire areas of study in India.

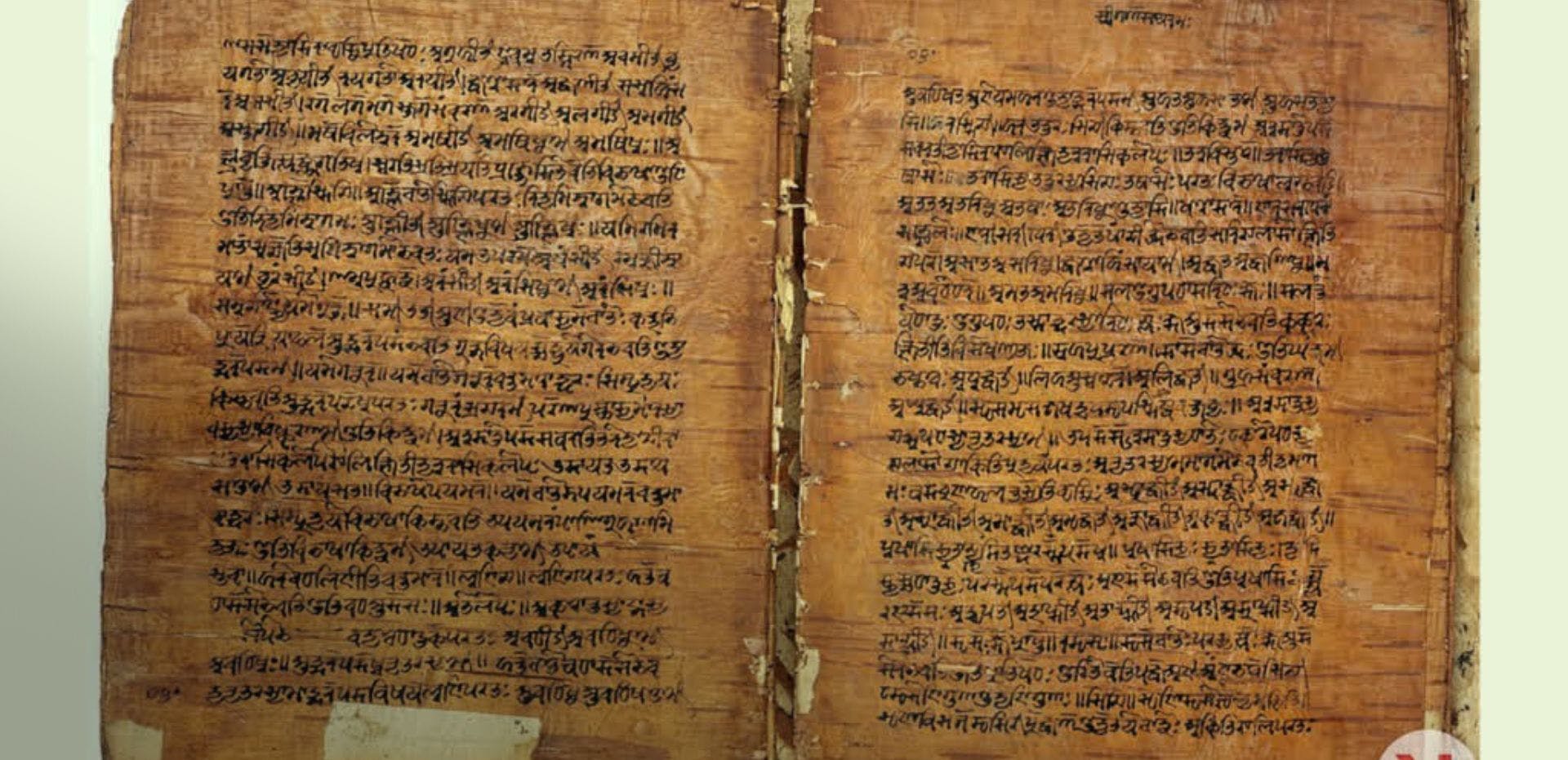

The period between the 6th century BCE and the 1st century BCE appears to have been a period of intellectual exuberance in which a vast body of work, on topics outside the purview of faith and religion, was done in the Indian subcontinent. These were scientific and practical works on a host of subjects like politics, economy, holistic wellness, medicine, mathematics, grammar and drama.

These works leaned heavily on even earlier works and went on to spawn further studies, through the ages. They were a culmination of existing knowledge and formed a nucleus of future technical literature. What is amazing is that much of it, like Chanakya’s practical advice, is as relevant today as it was then. Sadly, none of the original manuscripts from that period remain, but we do have numerous references to them down the ages as others built on what these ancient greats had penned.

Sushruta Samhita (6th century BCE)

Ayurveda, the traditional system of Indian medicine, is becoming the hottest fad around the world. From turmeric latte to drumstick leaves (dubbed as the world’s new wonder drug), everyone is ‘discovering’ herbal remedies that have in fact been passed through generations for centuries in India. In fact, the field of medicine in ancient India was so advanced that a text written 2,500 years ago by Sushruta, a sage from Kashi, mentions 1,120 medical conditions, 700 medicinal plants, 400 surgeries and 121 surgical instruments!

The text he wrote, Sushruta Samhita, stresses that “theory without practice is like a one-winged bird that is incapable of flight”. He was one of the earliest known medical teachers in the world to advocate that the dissection and study of dead bodies was a must for any successful student of surgery. At a time when biochemical or imaging equipment didn’t exist, Sushruta and his students carried out complicated surgeries like cataract extraction and removal of urinary stones (ashmari). During the procedure, they advocated medicated wine for anaesthesia and stressed sterilising the operation room by fumigating it with fumes of mustard, butter and salt.

One of the most interesting aspects of Sushruta Samhita is the sheer detailing of rhinoplasty (or plastic surgery for reshaping the nose) as a technique. Cutting off the nose of a criminal was a common punishment in ancient India and the text mentions more than 15 methods to repair it. These include using a flap of skin from the cheek or forehead, which is akin to the most modern technique today! There are also references in the text to the technique of moulding false legs with iron, now common as prostheses.

Another seminal work on medicine was Charaka Samhita authored by Charaka, a physician at the court of Kushan ruler Kanishka (2nd century CE) in Kashmir. It is, however, believed to have been an adaptation of a much earlier work, the author of which was Agnivesa, who was a disciple of the famous professor Atreya (6th century BCE) at Taxila. Concepts like ‘healthy mind, healthy body’ and ‘prevention is better than cure’, which are widely accepted today, appear in Charaka Samhita. Charaka is generally considered as the first physician to present the concepts of digestion, metabolism and immunity.

Charaka describes Ayurveda as:

हिताहितंसुखंदुःखंआयुस्तस्यहिताहितम्।मानंचतच्चयत्रोक्तंआयुर्वेदःसउच्यते॥

“That is named the science of life (Ayurveda), wherein is laid down the good and the bad life, the happy and the unhappy life, and what is wholesome and what is unwholesome in relation to life, as also the measure of life.”

Notice how the medical treatise talks about ‘life’, and not merely ‘health’?

Panini’s Ashtadhyayi (5th/4th century BCE)

Another treatise that cannot be missed when talking about ancient Indian literature is Panini’s Ashtadhyayi dated to the 5th/4th century BCE. It is a composition that has attracted the attention of Western and native linguists alike. It is the oldest surviving book on Sanskrit grammar and sums up the rules of the language in 3,996 sutras (phrases) detailing linguistics, syntax and semantics.

The text, which takes its names from the eight chapters that it comprises, details a scientific system of word analysis in the Sanskrit language and has no parallel in any contemporary work across the world. The book marked the transition from Vedic Sanskrit to classical Sanskrit.

Panini is believed to have hailed from a place called Shalatura in Gandhara and, according to legend, was given the gift of knowledge by Lord Shiva. An abundance of texts from around this time mention the Gods as the basis of their work, probably to give them legitimacy.

What’s interesting is that although this is a book on the intricacies of grammar, Panini referred to many aspects of his time – places, people, customs, weights and measures, beliefs, commerce, etc. He thus shed light on the social life of the period.

Sanskrit scholar Vasudeva Saran Agrawala, a student of noted Indian historian RK Mookherjee, has conducted a detailed analysis of the non-grammar part of Ashtadhyayi in his book, India As Known to Panini. He writes that a frequent geographical term used by Panini to describe a state was ‘janapada’. He also uses the term ‘varna’, pointing to the fact that society in those times was based on Varnashramadharma i.e. castes and ashramas or stages into which life was divided.

For example, Panini writes that ‘The house holder's life began with marriage. Its ceremony was performed round the fire as witness.’ Panini refers to marriage by the word upayamana, which he explains as sva-karaṇa, i.e. 'the bridegroom making the bride his own'. The marriage ceremony was solemnized by paṇigrahana, 'the holding by the bridegroom of the bride's hand'.

Ashtadhyayi acquaints us with an interesting list of economic products such as silk fabric, hemp, indigo, gems like emerald and ruby, iron chains and skins of tigers and leopards used as upholstering material for chariots, that was used at the time.

Other texts which became a core part of the Vyākaraṇa (grammar) canon were Katyayana’s Varttikakara and Patanjali’s Mahabhasya from the 2nd century BCE. Both of them acknowledge their respect for Panini by giving him the honorific ‘bhagavan’. All these works deconstructed words and sentences and presented them in a way that minimum syllables could be used to convey maximum information.

Arthashastra – The Science of Wealth (4th century BCE)

The most well-known text from ancient times has to be this one. Although the literal translation suggests that the work focuses on economics, the ‘wealth’ it alludes to relates to a wider spectrum that for convenience can be clubbed as a ‘guide to statecraft’ – how to build a kingdom, manage it and expand its dominions.

Mostly attributed to Chanakya, the story goes that it was born of vengeance. Kautilya was a minister in the court of Dhanananda, the ruler of the Nanda dynasty, which ruled the northern part of the Indian subcontinent. But a rift developed between the two and Kautilya was insulted. He vowed to topple the dynasty and leave his hair untied (he was a Brahmin) until he succeeded. Chanakya then met a young Chandragupta Maurya and helped him rise to become an emperor.

Divided into 15 volumes (150 chapters and 6,000 verses), the treatise covers topics like the nature of government, law, civil and criminal court systems, ethics, economics, markets, trade, diplomacy, theories on war, nature of peace, and the duties and obligations of a king. It also includes interesting insights into contemporary life – whether agriculture, mineralogy, mining and metals, animal husbandry, medicine, forests and wildlife.

A practical guide to the survival of the king, the Arthashastra also carries detailed instructions on foreign policy and espionage.

With regard to the economy, he says, ‘Cultivable land is better than mines because mines fill only the treasury while agricultural production fills both the treasury and the storehouses.’ He also specified, ‘The manufacture of alcoholic liquor was predominantly a state policy, except for the ones used for medicinal purposes…” The alcoholic drinks listed in the Arthashastra include medaka from rice, prasanna from barley flour, asava from sugarcane juice, maireya from jaggery, madhu from grape juice and arishtas for medicinal purposes.’ This gives us a glimpse into what the people of the time were consuming.

‘Conquest’ was an action that Kautilya stressed. He quite definitely said that a king’s job is to conquer, or be conquered. He said that an ideal king is one who agrees on a peace treaty one day and attacks the next. Nothing, absolutely nothing, should hinder invasion or conquest. For being upright and ethical, he cites the example of trees. In a forest, it is always the straight trees that are cut down, not the crooked ones. Kautilya believed that those who trust in fate or rely on superstition perish. His philosophy calls for action, not resignation. He believed in opportunism and that the end justifies the means.

The Arthashastra states very categorically that artha (material well-being) is superior to dharma (spiritual well-being) and kama (sensual pleasure) because the latter are dependent on it. This was quite revolutionary for the age that followed the Vedic era, which focused on righteousness. It openly talks about when violence is justified, how to test one’s family members and ministers, and how a king should be interested in the welfare of his citizens for selfish reasons. The economic wellbeing of the people provides resources to pursue conquest.

But we must not judge the characters of the past by modern yardsticks of morality. That was a time when the socio-political environment was very different. Petty quarrels among small states created chaos and political disorder. There was a need for stability which would have only been established with a powerful, centralised authority under the Mauryan empire.

We also must remember that in the Arthashastra, Kautilya mentions all this from the point of view of a hypothetical state. There is no mention of names of kings or kingdoms. However, this doesn’t take away from the fact that Kautilya was a master of knowledge and far ahead of his time. And his magnum opus was one of the great works being churned out in the subcontinent in ancient times.

Arthashastra became half the basis of one of the most important law books of Hinduism, Manusmriti. The other half was derived from the Dharmashastra. The Manusmriti is a discourse given by Manu and Bhrigu on topics such as duties, rights, laws, conduct, virtues and others.

Vatsyayana’s Kamasutra (3rd century BCE)

Popularly known as a ‘sex text’, many don’t realise that it is, in fact, much more than that! It is a manual on the art of living, besides prescribing methods to derive sensual pleasure. It is a complex treatise about finding a partner, maintaining power in a marriage, committing adultery, living as or with a courtesan, and of course, eroticism.

The Kamasutra provides us information about the conventional ideas of gender of the time it was written in. Vatsyayana says, “By his physical nature, the man is the active agent and the young woman is the passive locus, the agent contributes to the action in one way and the locus in another. The man is aroused by the thought, ‘I am taking her,’ the young woman by the thought, ‘I am being taken by him.’ ”

The Kamasutra states that progeny, fame and social approval are obtained by a man who marries a virgin of the same varna, according to religious rites. Vatsyayana refers to princesses and other elite women learned in the shastras, and lists 64 arts that should be learnt by women. These include solving riddles, completing poetic verses, the art of spreading flowers on the bed, producing music by striking glasses of water, carpentry, teaching parrots to talk, and impersonation.

Bharatamuni’s Natyashastra (2nd century BCE)

This is a text devoted solely to the production, technique and importance of music, dance and drama. The Natyasastra says that drama is natyabhavanikritam, or the reconstruction of reality, and hence is a process of sahanakirana (becoming one with the being and the process of it).

Regarding its origin, the text tells us that the natya was created as a plaything and to divert minds weary of problems, conflicts and miseries of daily life. It tells us that the text was passed on by Brahma to a sage named Bharata as a fifth Veda in order to save the world from evil passions.

It is interesting to note that the Natyashastra prescribes that in Sanskrit drama, the ‘high’ characters such as kings, ministers, etc. speak in Sanskrit, while the ‘low’ characters such as women (even queens) and servants generally speak in Prakrit.

G K Bhat, in his Bharata-Natya-Manjari: Bharata on the Theory and Practice of Drama (1975) writes that one of the central concepts discussed in the Natyashastra is rasa. The text uses the analogy of cooking to explain the art and effect of drama. The combination of various foodstuffs, vegetables, sweeteners, and spices gives food taste and flavour, which in turn produces delight and satisfaction. Similarly, in drama, the combination of the causes and effects of emotions give rise to a particular rasa or aesthetic experience in the audience, leading to pleasure and satisfaction.

According to Bharata, the auditorium should be divided into two main parts of equal length. The east part was meant for the audience hall and the western part was divided into two parts – the Rangasirsa and the Green Room. The Rangapitha was the stage and the Ragasirsa was the surface.

The text says that death should never be portrayed on stage, besides eating, fighting, kissing and bathing. The play should always end on a positive note. Unlike Greek drama, Sanskrit drama does not have a tradition of tragedy.

Natyashastra was truly scientific in spirit and artistic in expression.

Yoga Sutras of Patanjali (2nd century BCE)

Patanjali is known more for his renowned Yoga Sutras, than his work on grammar. Consisting of fewer than two hundred verses written in an obscure if not impenetrable language and style, this text today is extolled by the yoga establishments as a classic and guide to yoga practice. But what’s to note is that his book was much more than what yoga is perceived as today. Asanas or yoga postures was only one element of it. Patanjali’s yoga was all about becoming ‘one’ and the union of all the elements of the body.

Patanjali defines yoga as having eight components - yama (abstinences), niyama (observances), asana (yoga postures), pranayama (breath control), pratyahara (withdrawal of the senses), dharana (concentration), dhyana (meditation) and samadhi (absorption).

The most important thing to note about the Yoga Sutras is that they are built on a foundation of Samkhya philosophy, one of the six major philosophies of India. Originally written in Sanskrit, Samkhya describes the full spectrum of human existence by revealing the basic elements that make up the macrocosm and the microcosm. Samkhya teaches us about the components of the body, mind, and spirit, from the gross elements that make up the physical body to the more subtle elements of the mind and consciousness.

Samkhya names each element, teaches us its function, and shows us the relationship each element has to all others. It is effectively a map of the human being. Patanjali takes the Samkhya philosophy into the realm of experience, through gradual and systematic progression. Patanjali’s work remains robustly secular and moreover, espouses the Samkhya belief that “the existence of god or a supreme being is not directly asserted nor considered relevant” to the practice of yoga.

These are just some examples of the great works that emanated from this period and also indicate the body of work that had already been passed on, for generations by then. These works were a culmination of already existing knowledge and nucleus of future studies and technical literature. So what coaxed the ancients into a sudden frenzy of expansive thought?

There is no clear answer to this but we do know that great centres of learning, like Taxila, Kashi and Pataliputra, attracted scholars from across the Indian subcontinent. These ‘university towns’ acted as centres of discussion, debate and research, and it is from here that many of these works emanated.

It must be noted that many of these works must have been liberally added to over the centuries and it is difficult to give them an exact timeframe. However based on references and cross references scholars have some idea of the period during which these texts were first compiled. What stands out, is the wide array of subjects that scholars were working on in the period and how this set the stage for future works. Take for example Pingala’s work Chandaḥśāstra ( 2nd BCE) on Sanskrit prosody or the patterns of rhythm and sound used in poetry which was expanded upon by the mathematician Halayudha in the 10th CE, or works on astrology by Aryabhatta in the 5th century CE, and architecture by Varahamihra in the 6th century CE). The early scholars set the tone and stage for all these great works and what is amazing is how so much of this, has stood the test of time!

This article is part of our 'The History of India’ series, where we focus on bringing alive the many interesting events, ideas, people and pivots that shaped us and the Indian subcontinent. Dipping into a vast array of material - archaeological data, historical research and contemporary literary records, we seek to understand the many layers that make us.

This series is brought to you with the support of Mr K K Nohria, former Chairman of Crompton Greaves, who shares our passion for history and joins us on our quest to understand India and how the subcontinent evolved, in the context of a changing world.