Mangaluru’s Jewish Connection

BOOKMARK

While much has been written about the Jewish heritage of Cochin and Mumbai, few know about the fascinating Jewish connection with Mangaluru. The discovery of letters hidden in a wall in faraway Cairo in 1896 shed light on a forgotten chapter of Mangaluru’s history, going back to the 12th and 13th centuries.

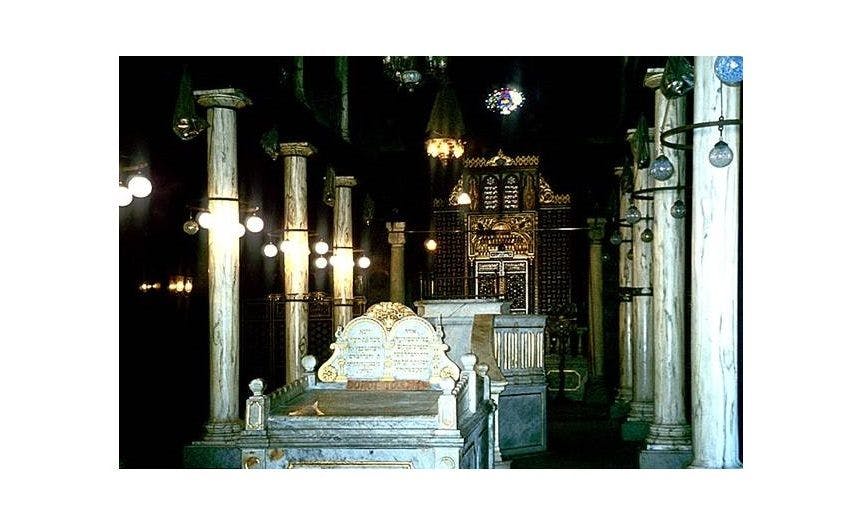

In 1896, Solomon Schechter, a Cambridge University scholar, jumped down into the dusty storage room of the Ben Ezra Synagogue in Cairo, Egypt, and found himself in a massive secret chamber filled with parchments (around 3,50,000) of great antiquity.

According to Jewish tradition, Hebrew is believed to be the language of God. For centuries, everyday documents written in Hebrew were not discarded but kept in repositories inside synagogues. They were called ‘genizah’. The documents found by Schechter became world famous as the ‘Cairo Genizah’ letters, which continue to intrigue scholars from around the world.

Decades later, in the mid-20th century CE, there was a growing interest in Aden’s (a port in present-day Yemen) mixed Jewish population, which could be traced to the medieval Cairo-Yemen-India trade connection. This led S D Goitein, a German-Jewish historian and ethnographer, to study the Cairo Genizah documents in 1948. They revealed a fascinating Jewish connection with Mangaluru in the 12th and 13th centuries CE.

From these letters, we know of the ‘Ben Ezra Jews’, who had settled in ‘Manjarur’ or Mangaluru. The Ben Ezra Jews were originally Tunisian Jews who had settled near the Ben Ezra Synagogue in Old Cairo in the 1100s. The Fatimid dynasty (909–1171 CE), which ruled Egypt at the time, were great patrons of trade with India, through which they drew much of their wealth and power. Through a systematic policy of state patronage, the Fatimid rulers encouraged Jewish merchants to establish a base in Mangaluru, which was famous for its trade in betel nut and black pepper, which grew in the hilly hinterland of this region.

In the early 1120s, the Ben Ezra Jews arrived on the shores of Mangaluru by sea, 3,243 km from Aden. Mangaluru, on the Indian West coast, was located smack opposite Aden on the Arabian Peninsula. The two ports, on opposite shores, aligned almost in a straight line. All the Ben Ezra Jews had to do was pick the right month for travel – June, when the monsoon winds, which originated on the East African coast in March, picked up pace and pushed their ships easterly from Aden, straight towards Mangaluru. They also had an agent or a ‘wakil’ stationed in Aden to look after their interests there.

In the 12th century, Mangaluru’s unique topography, being diametrically opposite that of Aden, distinguished it from the other port towns on India’s western coast. Mangaluru is also located at the confluence of two rivers – Netravati and Gurupura – which then drain into the Arabian Sea. This forms a backwater that makes the Mangaluru port navigable. The Gurupura river also runs parallel to Mangaluru’s shoreline, creating a barrier split that separates a part of the shoreline from the town and thus provides an extra layer of protection.

The Netravati river, which flows along Mangaluru’s southern end, runs deep into the hinterland, where black pepper and betel nut (supari), its main export goods, were cultivated. The trade barges carried these goods to the mouth of the confluence and exported them to the Arabian Peninsula to the west of Mangaluru. Geography couldn’t have been kinder to the Ben Ezra Jews who settled here, and to local merchants.

The Cairo Genizah letters revealed that many Ben Ezra Jews had moved from Old Cairo to Aden in the early 12th century and later settled in Mangaluru. Prominent among these was Ben Yiju, a Tunisian Jew who lived in Mangaluru for close to two decades, from 1132 to 1149 CE. Here, he constructed a bronze factory and also married his slave, Ashu, a local Tulu woman with whom he had three children.

It is Ben Yiju’s correspondence with Madmun B Hasan-Japheth, a Jewish merchant who had settled in Aden, that comprises most of the Genizah collection of letters on ‘India traders’. These letters give us a very important insight into the thriving international trade in Mangaluru. They speak of betel nut as the prime commodity that was exported from Mangaluru to Aden in the 12th century CE. Betel nut was called ‘faufal’ by Arab and Jewish traders, which was probably derived from their Sanskrit equivalent ‘pugaphala’.

Historian Stewart Gordon in his book When Asia Was The World gives an account of what Mangaluru was like in the 1130s. The port town had fortified merchant houses that were clustered close to the shore, where the harbour lay at the mouth of the river. A heterogeneous group of Jews, Arabs, Tamilians and Gujaratis had settled there and were around 2,000 to 3,000 in number. He adds that the black pepper for export came from the ‘green hills of the Western Ghats’, where it grew natively and was exported for the purpose of flavouring and its use in medicine.

In addition to pepper, there was also a thriving trade in minerals. JNU Historian Ranabir Chakravarti in his research paper, ‘Indian trade through Jewish geniza letters (1000–1300)’, mentions the regular trade of raw iron from Mangaluru to Aden and suggests that the mineral came from the Nilgiris and/or the Karnataka plateau. He quotes a letter sent from Madmun to Ben Yiju in Malabar in the 1130s, which reads:

‘As for iron, this year it sold (well) in Aden—all kinds of iron—and in the coming year there will also be a good market because there is none left in the city. Please take notice of this.’

While the Jews were just settling in Mangaluru, a number of conquests in the far West turned the tables for them. In the early 1140s, the Fatimids of Egypt lost their power. Similarly, wars broke out between Egypt and Yemen (where Aden is located). The resultant instability disrupted the Egypt-India trade and most of the Jewish merchants left Mangaluru for their homeland in 1147 CE.

Mangaluru’s Jewish connection was completely forgotten till the discovery of the Genizah letters. Interestingly, only a very small fraction of the 3 lakh letters has been translated, leaving so many chapters of global and Indian economic history waiting to be uncovered.

Cover Photo: Interiors of the Ben Ezra Synagogue by Roland Unger / Wikimedia Commons