The Other ‘Shakespears’ in India

BOOKMARK

Say the word ‘sonnet’, mention Stratford-upon-Avon, think of star-crossed lovers and invariably your thoughts will turn to William Shakespeare (1564-1616). He wrote into history phrases we still use every day, even if we don’t know that’s where we get them. Which is why it’s strange that so little is known of the branch of the Shakespear family that headed to colonial India – and spent decades here working with the East India Company, writing, serving in the colonial-era army, and mingling with Indian royalty and British litterati.

William Shakespeare’s grandparents Richard and Abigail had five children – Henrye, Anna, John, Thomas and Matthew. John Shakespeare and his wife Mary were the parents of the Bard of Avon. The Shakespear family (read on to find out why they dropped the ‘e’) flowed, in all likelihood, from William Shakespeare’s uncle Matthew, through his son Thomas. The descendants of this line of the family are also known as the ‘Shadwell Shakespears’. They had a family history in the rope-making business, and boys in every generation tended to be named John, Matthew, William or Thomas.

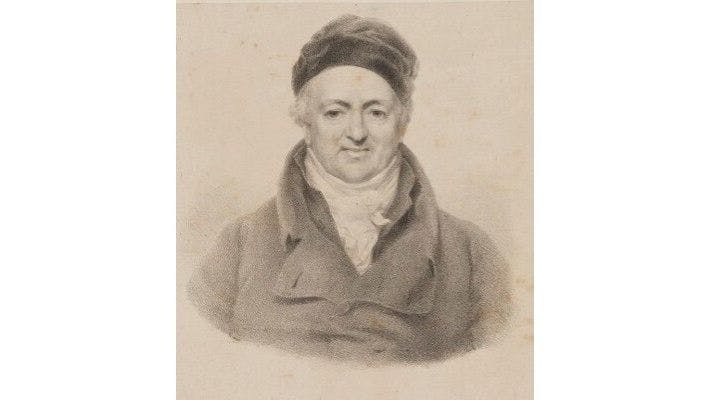

John Shakespear (c. 1749-1825), the great-great-grandson of Thomas, son of Shakespeare’s uncle Matthew, was a close associate of Warren Hastings, Governor-General of Bengal. And thus started the long association of the Shakespears with India.

Xiao Wei Bond, Curator of the India Office Private Papers at the British Library, in the Untold Lives blog of the archive, writes, “Among the generous benefactors to India Office Private Papers is the late Dr Omar Pound (1926-2010), teacher, writer and translator of Persian and Arabic literature, only son of the celebrated American poet Ezra Pound and his English wife, artist Dorothy Shakespear (1886-1973). Ezra and Dorothy met at the salon of her mother Olivia Shakespear (1863-1938) who was a life-long friend and one-time lover of W.B.Yeats. Olivia was a novelist and playwright in her own right and an influential patron of the arts. Her Kensington salon was frequented by writers and artists including Pound, T S Eliot, and James Joyce…

“The Shakespear family,” the blog continues, “is related to a number of other illustrious figures in English literary and military history in British India, including William Makepeace Thackeray, General Sir John Low, and Colonel Sir Richmond Campbell Shakespear. In order to avoid confusion with William Shakespeare, the Shakespears of British India dropped the ‘e’ at the end of their name. There is, however, a distinct possibility that their earliest traceable ancestor John Shakespear of Shadwell could well be from the same stock as the great poet of Stratford.”

John Shakespear started out as a junior civil servant with the East India Company but by 1778 was Chief of Council for the EIC at Dacca. He was only 29. He left India in 1780, after amassing considerable wealth. And his return journey is one of those tales of adventure, rivalry and intrigue that would be worth a play in itself.

Before he returned to England, John was handed a confidential letter from Warren Hastings, the then Governor-General of Bengal, to Laurence Sullivan, the Chairman of the Court-of-Directors of the East India Company, regarding disputes over jurisdiction that had made their way to the Supreme Court in England.

Sir Philip Francis, the Irish-born British politician of the Whig party and the chief adversary of Hastings at the time, was in ill health not having yet recovered from the effects of a recent duel with Hastings, and was against Hasting’s proposed actions in relation to the jurisdiction disputes. Theirs was an eternal rivalry.

So, as John headed back to England by sea, carrying Hastings’ letter, Francis followed on an accompanying vessel of the same fleet, desperate to reach England before Hastings’s letter could reach the Company bosses. He wanted a chance to campaign in person against Hastings, before the Company’s Court of Directors. Word of this reached John, and so when the fleet of English ships reached the British territory of St Helena in the South Atlantic Ocean, John Shakespear gave Philip Francis the slip by boarding a Dutch vessel that was leaving port immediately.

He reached England four months ahead of Francis, and accounts of this race by sea can still be found in a book by Ursula Low, a relative to the Shakespears in India, titled Fifty Years With John Company, originally published in 1936 (John Company was an informal name by which the EIC was known).

Upon his arrival in England, Hastings presented John with a statuette of the Bard in appreciation, an heirloom that remained in the family for a very long time. But Philip Francis would have the last word in a sense. His accusations led to Hastings being impeached before Parliament on his return to England, on charges of embezzlement and extortion, among other alleged crimes. And while the impeachment was unsuccessful it cost Hastings so much money to defend himself that he frequently remarked that it would have been cheaper to plead guilty.

Who Goes There!

Another story recorded about John Shakespear and Warren Hastings is even more Shakespearean – and involves the ghost of a dead father.

Just before John Shakespear was to leave Calcutta, Hastings and his men were hard at work in the office as the day drew to a close. The silence of the room was unceremoniously shattered by a scream let out by John. “Good lord! That’s my father!” he reportedly said. Everyone in the room looked up, including the no-nonsense Governor-General, and legend has it everyone saw an elderly gentleman gliding across the room towards the window. Joseph Cator, Hastings’s personal secretary, narrating this story at a later date would say that they all noted that the apparition was wearing a strange sort of hat. No one yet had seen that hat in India; it was a new design known as the ‘Chimney Pot’, a sort of hybrid of the top hat and bowler.

When the apparition had gradually dissolved into the evening air, Hastings was the first to recover his wits. He immediately instructed that an official record be made of the sighting. That done, little further work was completed and everyone retired.

A few weeks later a ship arrived in Calcutta that brought unhappy news. John Shakespear’s father had died. The ship also brought a cargo of the newest haberdashery trend back home – Chimney Pot hats. The written record that Hastings advised be made has never been found. Yet, more than a century later, in the early 1900s, descendants of both the Shakespear and the Cator families in England recounted to separate interlocutors almost identical family lore about the event.

Young Blood

While in the service of the East India Company, John forged friendships with William Makepeace Thackeray Sr (the grandfather of the famous author of the same name) and Robert Low of the Madras Army. The association of these three families would continue in India and in England for the next 200 years.

The extended families of the Shakespears, the Thackerays and the Lows intermingled through marriage, military duty and social patronage. Members of these families also engaged actively in the Imperial and Indian Civil Services; some joined the British Indian Army, others worked as jurists, journalists and writers. There is so much curiosity about this association, in fact, that dozens of books have been written on the lives of the members of these families.

John’s son John Talbot Shakespear married Emily Thackeray, daughter of William Makepeace Thackeray Sr, and was aunt to the novelist and satirist William Makepeace Thackeray Jr. The Shakespear-Thackeray wedding was held in March 1803 at St John’s Church, Calcutta. At the time, John Talbot was Assistant Collector of Birbhum. John Talbot and Emily had nine children. Three of their sons were involved in the British Indian Army (incidentally, one was also given the family name of William Makepeace, except he was William Makepeace Shakespear).

George Trant, another of their sons, was a non-military person immortalised in other ways. It is popularly believed that ‘Roly Poly’ George was nicknamed ‘Polar Bear’ for his weight and rolling gait. “The portrait of Jos Sedley (in William Makepeace Thackeray Jr’s masterpiece, Vanity Fair) – fat, lazy and overdressed – is certified…as an overcoloured picture of George Trant Shakespear,” Ferdinand Mount writes in his book The Tears Of The Rajas: Mutiny, Money And Marriage in India 1805–1905 (published in 2015).

John Talbot and Emily’s daughter, Augusta, married Sir John Low, the British Resident in Lucknow during the critical years preceding its annexation. He was a descendant of Robert Low. The story of Sir John Low and his family forms a large part of Mount’s book.

The Shakespears and Thackerays, two huge families, lived not far from each other, in villas on Alipore Road in Calcutta that were the scene of regular merry-making. Emily was known for throwing elaborate and lavish parties for all of White Town.

It was in Alipore that William Makepeace Thackeray Jr was born, to Emily’s brother Richmond Thackeray and his wife Anne Becher. Richmond Thackeray would eventually be Collector of the 24-Parganas.

Emily Shakespear died in Calcutta in 1824, aged 40, from cholera and is buried at the South Park Street cemetery. Close by, in the same cemetery, is a memorial to her husband John Talbot, who died and was buried at sea in 1825.

Of their four sons, John Dowdeswell Shakespear would become a colonel and serve at various positions with the Company. After he left India, however, nothing more was known of him except that he died in London. The second son, William Makepeace Shakespear, died at 28 while with the British Army and is buried in Lucknow. He was serving under his brother-in-law, Sir John Low, his sister Augusta’s husband. The third, George Trant, committed suicide in Geneva in 1844. The fourth and youngest son, Col Sir Richmond Campbell Shakespear, began a line that would remain prominent in the army and Civil Services in India.

The Bhopal Affair

Sir Richmond Campbell Shakespear played a pivotal role in cementing British ties with the royal family of Bhopal. It was the 1850s and Sikander Begum was claiming the title of Nawab of Bhopal over her daughter, the named heir, and this had caused a rift within the royal family. The British were backing her claim because the State of Bhopal was strategically vital to their interests – and she had proved a very loyal supporter.

She had supported the British during the Revolt of 1857. To prevent rebellion in Bhopal, she banned the publication and circulation of anti-British pamphlets. She prohibited anti-British meetings and gatherings. She had used her state’s intelligence network to help the local British administration, and motivated anti-British soldiers to switch sides. They had, in fact, had to help defend her when angered by her pro-British stance and encouraged by rival members of the Bhopal royal family, a group of anti-British Indian soldiers had surrounded her palace in December 1857, determined to throw her out.

In 1859, then, Richmond Campbell Shakespear was sent to Indore as the political agent to the Governor-General for Central India, to try and help Sikander Begum secure the title she sought. By then, Richmond was known among the British for his excellent rapport with Indian royal families. Bhopal was the second-largest princely state in pre-Independence India, after Hyderabad, and was centrally located. So Richard Campbell took care to build a solid interpersonal relationship with Sikander Begum. He conducted a year-long negotiation with the Nawab Begums of Bhopal and installed Sikander Begum as Nawab of Bhopal in 1860.

He managed to convince Sikander’s daughter Shah Jahan Begum not to contest the claim in the end, and as a result of this resolution, British rule in Central India was stabilised.

Richmond Campbell Shakespear died in Indore in 1861, just two months after the birth of his youngest son, John Shakespear. On the announcement of the death, William Makepeace Thackeray Jr wrote in his popular column – Roundabout Papers – On Letts’s Diary: “We were first cousins, had been little playmates and friends from our birth… when he came to London the cousins and playfellows of early Indian days met him once again, and shook hands. “Can I do anything for you?” I remember the kind fellow asking. He was always asking that question: of all kinsmen; of all widows and orphans; of all the poor; of young men who might need his purse or his service.”

In a rather full-circle moment, it was Col Sir Richmond Campbell Shakespear’s son, John Shakespear, who preserved and publicised his grandmother Emily’s writings, which were published in a journal called Bengal Past and Present in 1910, which in turn is preserved in the West Bengal state archives even today.

This John Shakespear was a decorated officer of the British Army in India, an Indian Political Service officer, and a keen historian. He wrote two books on the early history of Mizoram and its people. His detailed notes on the State of Manipur and its royal family are preserved in the British Library archives. And even today, research theses are submitted at Mizoram University on John Shakespear and his works. He was also keenly interested in the history of the Shakespear family in India.

The journal of Emily Shakespear that he helped preserve contained a spectacular travelogue that recorded details from her journeys with her husband John Talbot. He, in his then capacity as Police Superintendent of Bengal, Bihar, Orissa and part of Upper India, had grown very close to the Governor-General of Bengal Francis Edward Rawdon-Hastings, also known as the Earl of Moira. John Talbot and Emily accompanied the Earl on his official tours up the River Ganga in 1814.

Her description of the procession of the fleet of 400 boats that accompanied Lord Moira on this tour is perhaps her most striking account. In this journal, she also wrote about the life of the ‘Dwadeeds’ (Dwaris, Sanskrit for Boatmen), who rowed the boats in which Lord Moira and the entourage sailed. And she wrote extensively about the city of ‘Moorshidabad’, the then Nawab of Bengal Zain-ud-Din Ali Khan, and the customs in his zenana or women’s quarters.

And so it is that through the diary of a woman who bore the names ‘Thackeray’ and ‘Shakespear’, we have an account of the life of a remarkable family, with roots traceable to a cousin of the Bard of Avon.

Cover photo: John Shakespear of Brookwood, courtesy: National Portrait Gallery

– ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Devasis Chattopadhyay is the author of Without Prejudice, a corporate reputation and brand management strategist, and a columnist.