The Indian Charivari and its Dirty Secret

BOOKMARK

Recently, there have been a series of discussions in the Supreme Court of India regarding the role of the media, in inflaming passions and bigotry. Many commentators have pointed out that several of the media publications have served as a front for those in power, to spread hysteria and peddle hate, in return for business favours. But you will be surprised to know that this is not a recent phenomenon. For, one of India’s earliest magazines too served such a purpose, with the proprietor happy to play along, as it served his own business interest.

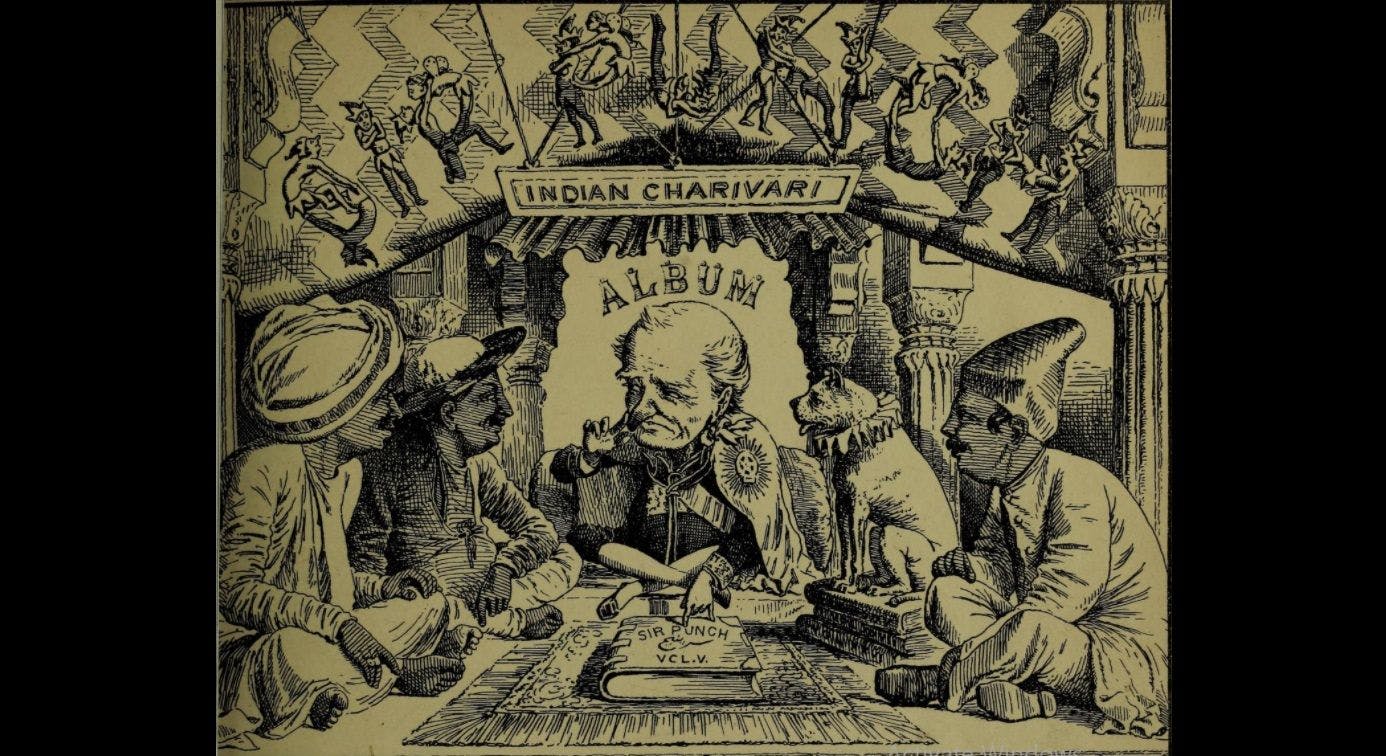

In the right hands, humour can hold up a mirror to society, it can be used to gently highlight our failings and to even encourage politicians to course correct. But such noble intentions were of no use to The Indian Charivari. The comic magazine, published from Calcutta in the 19th century and modelled on the famous English magazine Punch, was unabashedly racist and aimed its vitriolic wit at the ‘natives’ in general and the Westernised Bengali, in particular. Not surprisingly, it was a huge hit in circles populated by senior British civil servants, aristocrats and the wealthy British elite in colonial Calcutta.

Noted for its clever wit and superior production values, The Indian Charivari is now “regarded by scholars as being culturally important, and is part of the knowledge base of civilisation as we know it”, says e-commerce portal Amazon, where you can buy facsimile copies of this iconic publication.

So, what do you think the resume of the editor and proprietor of such a publication would look like?

There isn’t much archival material on his stint as editor, but Colonel Percy Wyndham is said to have launched and run The Indian Charivari in 1872. He is supposed to have been born on 22nd September 1833 on board a ship while it was in the English Channel. At the age of 15, he claimed to have fought in France to help usher in the Second French Republic. He was a soldier in the Austrian army. He served as a Garibaldi Volunteer in 1861, in the Italian Risorgimento, the ‘Rising Again’ movement, which helped create the modern state of Italy.

Subsequently, Wyndham fought valiantly in the American Civil War, between 1862 and 1864, as a Colonel in the Union Army. However, he was unceremoniously discharged as he was suspected of being in cahoots with the Confederates, to assassinate Abraham Lincoln! After his discharge from the Union Army, he opened a private military training school in New York City, and thereafter when it did not take- off, he also tried his luck with various other trading and manufacturing ventures, including a petroleum refining business. Not one of his business ventures succeeded.

This was a time when Europeans were making a beeline for India, a ‘land of opportunity’, to make their fortune. And could anything be more tempting than that for an adventurer, a mercenary and an opportunist like Wyndham?

He arrived in Calcutta and, obviously looked around for creating earning opportunities and according to archival material available, hey-ho, he launched one of imperial India’s most talked-about cartoon and comic magazines, The Indian Charivari, in 1872. But it seemed there was nothing Wyndham would not do – this career military man was also the impresario of a famous Italian opera company in Calcutta in 1874!

After he was embroiled in a controversy with the British administration, he left Calcutta for Mandalay (present-day Myanmar) to head the Burmese Royal Army. He died in Rangoon on 27th January 1879, at the age of 46, in a ridiculous accident, while experimenting with hot-air ballooning.

That was Colonel Percy Wyndham in a nutshell. It is believed that when he was only 15 he volunteered for the Student Corps in Paris. He subsequently obtained a commission in the French navy, followed by service with England’s Royal Artillery. In 1852 he left England to become an officer in the Austrian Lancers, where he served for two years before joining the hero of Italian unification, Giuseppe Garibaldi. Under Garibaldi, he rose rapidly to the rank of lieutenant colonel and was knighted for bravery.

Tim Kent in his Civil War Tales – Just Different Blogs From A Lifelong Civil War Historian, on 16th January 2017, a well-known blogger on American Civil War, wrote, “Wyndham was very tall, always dressed nice, famous for his 10-inch-long moustache and a bit of a show-off”. Wyndham’s photograph, being preserved among the veterans of the Civil War in the Library of Congress in the US, supports the statement. Moreover, there are many testimonials, reports, and books available online about his life till he reached India. His exploits in the American Civil War are minutely documented. In Italy, too, his bravery is well recognised and written about.

But once he reached Calcutta, in the early years of the 1870s, nothing much was recorded about him except a few cryptic mentions about the launch of The Indian Charivari magazine, him marrying a wealthy widow (whose name nobody knows to date), being an Italian opera impresario, having a fight with a soldier in the bar room, losing his wealth and migrating to Mandalay to rebuild his fortune. Eventually, his death in a hot-air balloon crash was reported on 27th January 1879. It was as if the world had suddenly suffered collective amnesia for Wyndham’s time in Calcutta.

It was strange, to say the least.

Why would a career military man and a mercenary establish and publish an iconic magazine in a faraway land, especially since he had shown not an iota of interest in matters literary or cultural? He would have been 39 years old when he launched The Indian Charivari and, just when the magazine started to pick up, he relinquished ownership of the publication and left India. Why would he have done that? What made him become an impresario of the Italian Opera in Calcutta when he had no experience in the creative or performing arts?

A brief look at The Indian Charivari will underline this anomaly.

Art historian Partha Mitter, in his article Cartoons Of The Raj published in History Today magazine in September 1997, wrote, “Of the English comic magazines, none was more accomplished than The Indian Charivari founded in 1872…What provided The Indian Charivari its cutting edge was racial malice. Caricature thrives on consensus, on a shared culture of ‘us’ versus ‘them’. The joke is shared and so is the hostility. The arresting quality of this comic magazine lay in its witty caricatures of the Bengali character, exploiting the existing views of the Westernised Bengali as a buffoon with touching pretensions to rival the rulers in intellect and culture.”

The British administration was very disdainful of educated Hindus, especially Bengali gentlemen (‘bhadralok’) after the Revolt of 1857. Their contempt was deep-seated because educated Bengalis questioned British superiority and tried to establish themselves as equals to British Civil Servants. The Indian Charivari’s ‘Baboo Ballads’, a series of caricatures, sneered at such ambitions. In fact, the magazine was especially incensed at contemporary vernacular papers such as the Hindoo Patriot and Amrita Bazar Patrika, which vehemently challenged racial slurs against Bengalis. The Indian Charivari hit out at these Indian publications through its editorials and sketches.

Radha Prasad Gupta, bibliophile, essayist and raconteur, in his essay The British And The Babus, provides a valuable perspective for the hostility on both sides. Gupta writes, “The Sepoy Mutiny of 1857 provided the British rulers with one of their most traumatic experiences in India. It undermined their faith in the loyalty of the Indians and intensified the feelings of racism. Words like ‘dirty niggers’ and ‘bloody natives’ were more frequently heard.”

This kind of racism was further aggravated by the rise of the English-educated Bengali middle-class and the ‘Ilbert Bill’, which sought to give English-educated native Magistrates the right to try a British national in a court of law in India. “Consequently, the English-educated Bengali Babus became an object of increasing ridicule and attack of the majority of the British in India. Possibly the most vitriolic examples of such attacks are to be found in the pages of the Anglo-Indian comic magazine, The Indian Charivari,” adds Gupta.

Currently, if you want to buy a facsimile reprint of a single issue of The Indian Charivari on the popular e-commerce portal Amazon, it will cost between Rs 1,500 and Rs 3,000.

A few years ago, Prinseps, a Mumbai-based auction house and an art gallery, sold five original issues of The Indian Charivari along with an annual album for Rs 1.8 lakh, and another lot in 2019, for an estimated Rs 2.5 lakh. The auction catalogue wrote: “Non-exportable item – The Indian Charivari was a magazine that was founded in 1872 as an illustrated paper that reviewed current political and social topics in a playful spirit. Often referred to as the ‘Indian Punch magazine’, it had caricatures of statesmen, military and public figures in India along with information about them. The magazine used parody and witty caricatures in their text and images to express their views on Indians and the British at the time.”

But why would a soldier with no roots or family ties in India and who fought to abolish slavery in the American Civil War suddenly turn racist? Was it a ploy to boost the magazine’s sales? Or was it something different?

It is not surprising that Wyndham chose to come to Calcutta. There were many adventurous men and women and those who sought to make a fortune who landed in Calcutta after the Revolt of 1857, when the British Crown took control of India. Considering how many Englishmen had made it rich after stints in India, this country was considered the new Eldorado.

But, of all the things he could have done, why did Wyndham choose to launch a comic and cartoon magazine? And he appeared to have excelled at it, both editorially as well as commercially! How was this possible in a land where he had no real network and that too with a subject of which he had demonstrated no prior knowledge? Besides, who wrote for his magazine and who created the sketches and cartoons? Who was the editor? Where was it printed? Even the office address – ‘7 Dacre’s Lane’ – was incorrect.

In fact, these questions were repeatedly asked in the ‘Letters to the Editor’ column in The Indian Charivari and in various contemporary newspapers. If one visits the ‘Rare Book Section’ of the Indian National Library in Kolkata, and accesses copies of The Indian Charivari today, apart from its racist overtones, the most intriguing part about the magazine is the secrecy with which the management conducted its affairs.

The magazine did not disclose the names of its contributors, not ever. One might even say that the management of The Indian Charivari deliberately misled the public about the functioning of this periodical. The imprint line always stated that ‘this periodical was issued from The Charivari Press’, hinting that the periodical was printed there as well. Surprisingly, no directory in Kolkata has ever listed an address for ‘The Charivari Press’. Simply put, it did not exist.

Why the utter secrecy? The mystery deepens.

The Thacker’s Bengal Directories for the years 1873 to 1880 yielded some answers. For the first four years of its existence, from 1872 to 1876, The Indian Charivari was printed at The City Press, 12 Bentinck Street, Calcutta. In 1877, it was printed at the Calcutta Central Press Limited, at 5 Council House Street; and in 1880, before the magazine finally shut that year, it was printed at the Exchange Gazette Press, 9 Council House Street. These were well-known printing companies capable of printing heavily illustrated and finely produced fortnightly publications like The Indian Charivari. And, according to the commercial custom of the time, they disclosed their client list to The Thacker’s Bengal Directories. So why the cloak-and-dagger attitude of the magazine’s management?

The Thacker’s Bengal Directories also disclosed Percy Wyndham’s address, as 5 Chowringhee Road, where Metro Cinema is now situated. This too was a revelation as his address had never been disclosed in the magazine as its proprietor. Incidentally, the present Metro Cinema building was inaugurated in 1935, replacing the building in which Wyndham lived, in the ‘White Town’.

The secrecy that cloaked The Indian Charivari was out of place also because other contemporary comic magazines in India delightfully flaunted their credentials. For instance, The Delhi Sketch Book, India’s first satirical magazine, was published from Delhi from 1850 till it was discontinued in 1857. Its founder-publisher-editor was John O’Brien Saunders, who became the proprietor of the famous newspaper, The Englishman in Calcutta in 1862.

The next comic magazine to launch was The Indian Punch in 1859, in Delhi, followed by The Bengali Punch titled Basantak (1874 -1876), which was published by Hari Singha and later by Rambramha Mukhopadhyay, and edited by Prananath Dutta.

One of the longest-running English language comic and cartoon magazines published by an Indian was The Parsi or The Hindi Punch (1878-1930) by Barjorji Naorosji of Bombay. He supported the Indian National Congress when it was founded in 1885. This magazine’s favourite personification of India was ‘Panchoba’, an Indian version of the figure of Mr Punch, while its style of illustration often reflected the English parent magazine.

The Oudh Punch from Lucknow (1877 – 1912 / 1916 - 1936), was a kind of an Urdu version of the English Punch magazine, was remarkable for its sarcasm and wit and was owned, published and edited by Muhammad Sajjad Hussain Kakorvi, a supporter of the Indian National Congress.

In contrast, the functioning of The Indian Charivari was always nebulas. What was it afraid of? What was it hiding?

Before we answer these questions, let us explore Percy Wyndham’s apparent musical leanings as a promoter of the Italian Opera in Calcutta.

Let us start with two advertisements published in the Indian Mirror newspaper, on the Italian Opera Ticket Lottery by Wyndham, in July and August 1874. The advertisements state that advance booking of season tickets for the season of 1874/75 had commenced and patrons could avail concessional rates by paying in advance and taking part in a lottery to be held shortly. The denomination of each ticket was Rs 10 each and there were a total of 735 tickets.

These advertisements make two things very clear. The first was that Wyndham was close to elite Bengalis because the Indian Mirror was primarily subscribed by followers of Debendranath Tagore, who was the founder of the Brahmo Samaj in Calcutta. Second, Wyndham was not considered racist by Bengalis or else the Indian Mirror would not have accepted those advertisements.

This brings us to the Italian Opera in Calcutta and how popular it was.

The Italian Opera was very popular in India during the 19th century, especially in Calcutta and Bombay, among Europeans, Rajas, Maharajas, and aristocratic and elite Indians, and it gave British Civil Servants in India and the administrators of the Bengal and Bombay Presidencies bragging rights over who had been treated to a better season.

The opera was usually held in winter and once the 1873–74 season ended, The Town Opera Committee in Calcutta started planning for the 1874-75 season. But there was a legal problem, with the existing impresario, Alessandro Massa, who at the last moment declined to bring in an opera for the 1874-75 season to Calcutta. This created a crisis for Calcutta’s Civil Servants and the snobbish elite, with the Opera Committee scrambling to find an impresario willing to fund and provide an Italian Opera Company for the forthcoming season. The Englishman newspaper, dated 4th May 1874, reported that Colonel Percy Wyndham had volunteered for the position and was “backed by a very powerful group of people”.

As we know, Wyndham had little to qualify him for the position: he was wholly inexperienced at opera management, and unlike the Italians before him, he agreed to act as impresario only if he were guaranteed a rather generous salary of Rs 2,100 (for seven months’ work). Despite these terms, Calcutta was so relieved at being saved the ignominy of having to cancel the 1874–75 season that the council accepted Wyndham’s conditions because he had the backing of “a powerful lobby”.

Wyndham sailed to Italy with Augusto Tessada, an Italian bass singer from Massa’s 1873-74 staff, who had stayed back in Calcutta and appeared to have acted as a sort of advisor to Wyndham. Once in Italy, Wyndham engaged his artistes through Carlo Cambiaggio’s opera agency in Milan for the Calcutta season 1874-75.

However, the season was a disappointment in terms of talent and production values. The Englishman newspaper, which was reporting on the opera episode on an almost day-to-day basis, stated that it was but natural, given Wyndham’s lack of experience. And, as the season drew on, the shortcomings of Wyndham’s company became increasingly obvious, and public opinion of the company deteriorated. Some even began to question Wyndham’s ability to manage a foreign opera troupe.

Wyndham’s career as an opera impresario was to come to an abrupt end, and it had nothing to do with how he had apparently mishandled Calcutta’s opera season. His downfall was his liberal attitude towards opera attendance and the social role of opera, which his backers did not appreciate.

The first of such follies was allowing soldiers in uniform to get tickets at concessional rates and allowing them to bring their wives at no cost. Wyndham was himself a soldier and these were the concessions of a kindred soul. He also felt that policies like this would democratise the opera and establish a broader base of patronage for the art form, both of which were necessary if the city wished to secure the opera’s future.

But Calcutta’s British elite was unhappy with the changes, as they felt they diminished the social and economic prestige that opera patronage represented. This intolerance was stretched to breaking point by Wyndham when he invited a ‘native’ Bengali theatre group to use the stage of the Lindsey Street Opera House (now Globe Cinema) to generate revenue. He offered to lease the Opera House to the theatre company, owned by Nagendranath Bannerjee, during off-season, to cover the cost deficit he was facing as the impresario to maintain the Opera House.

It was not the leasing of the Opera House that was unacceptable to the power brokers; it was outrageous that it should be leased to an upcoming Bengali theatre group, which was a product of the Bengal Renaissance – the educated Bengalis, the bhadralok, the 19th-century ‘state enemy’ of the English bureaucracy!

Remember, at this point, the unique selling point of The Indian Charivari was, to put it mildly, heaping scorn on ‘Bengali Babus’. As editor of the magazine, how could this have escaped Wyndham’s attention?

Anyway, returning to the opera debacle – Wyndham’s decisions created a huge debate and purge among the European residents of Calcutta. The split was bitter. The pro-Wyndham group comprised small merchants, mercantile clerks and military men, who were middle-class British. The anti-Wyndham camp, on the other hand, was led by the two most powerful members of the Imperial Civil Service (ICS), Justice Glover N J Valletta and Lieutenant-Governor Sir Richard Temple. It also attracted the support of Calcutta’s European minorities: the French, Germans, Italians and particularly the Greeks and the Armenians, who did not wish to displease the ICS cadre.

The Englishman newspaper, from November 1874 till June 1875, is choc-full of letters, reports and stories of this bitter tussle. Fed up with bureaucracy, power politics and continued controversy, on 6th April 1875, Wyndham finally published an advertisement on the front page of The Englishman, announcing that he would be interested to sell his impresario rights of the Opera Company.

Next we hear of Colonel Percy Wyndham, he’s in Mandalay!

The Annual Cyclopaedia and Register of Important Events of 1876, published by D Appleton in New York, was a comprehensive yearbook of international events, obituaries and statistics, with articles written by experts. This compendium confirmed Wyndham’s presence in Mandalay and reported that he had arrived there in 1875 after relinquishing control of The Indian Charivari. He was in Mandalay “to help the King of Burmah fight the Crown of Britain”.

Wyndham may have been many things but he did not seem to be racist. The Calcutta Opera episode had made that abundantly clear. Being a soldier, he believed in a fair fight, even though he was a mercenary. So, even if he fought someone else’s fight for money, he never compromised his beliefs or his conscience. For example, in the American Civil War, Wyndham fought for the Union Army. He fought in Risorgimento as one of Garibaldi's Volunteers. As impresario of Calcutta’s Italian Opera, he wanted to give the average soldier of the British Army and the middle-class of Calcutta the opportunity to watch and listen to beautiful renditions of the opera. He even took on a powerful lobby to do this.

So how could he have been the man behind The Indian Charivari?

A valuable clue to solving the mystery of The Indian Charivari comes from Sir Henry Cotton, who had a long and distinguished career in the ICS, during which time he was sympathetic to Indian nationalism. After returning to England, Cotton served as a Liberal Party Member of Parliament for Nottingham East, from 1906 to 1910. In fact, he had worked under Sir Richard Temple at one point, in India.

Critical information provided by Sir Henry Cotton in his book Indian And Home Memories (1911), about the ownership of The Indian Charivari, is worth quoting. “No Lieutenant-Governor was ever appointed to Bengal with a more distinguished record of service than Sir Richard Temple. He was the vital spark to an ephemeral comic newspaper started at this time, The Indian Charivari, of which, of all men, George A Grierson, probably the greatest of our modern Orientalists, was the leading spirit.”

The following year, i.e. in 1912, The Calcutta Review, confirmed that George G Palmar, Superintending Engraver in the Surveyor-General’s Office, used to sketch portraits of famous personalities for The Indian Charivari magazine, including the caricature of Sir Richard Temple, under the pseudonym ‘Isca’. In fact, civil servants of the Crown knew of this misadventure of Richard Temple but chose to keep quiet. The then state machinery supported the magazine from behind the curtain.

Sir Richard Temple (1826-1902) was a typical British civil servant and administrator known for his strong anti-India attitude but it would have been political suicide to parade his racist attitude in the open by acknowledging his role in the magazine or his association with Grierson.

None of the three books written by Temple – India In 1880, Men And Events of My Time and The Story Of My Life – refer to his association with The Indian Charivari, or Percy Wyndham, or Sir George A Grierson. He never wanted to admit knowing them.

Now we know, through the reportage of the acrimonious event of the Calcutta Opera in the dusty pages of old newspapers and through Rocha Esmeralda Monique Antonia’s book, Imperial Opera: The Nexus Between Opera and Imperialism In Victorian Calcutta And Melbourne (2012), that Sir Richard Temple not only knew Percy Wyndham, he knew him well. He did not approve of Wyndham supporting Indians and he was not only upset with him, but campaigned against him with the Opera Committee of Calcutta.

So, when his alleged main benefactor turned again him, Wyndham had to leave Calcutta. Moreover, once Sir Richard Temple left India in 1880, The Indian Charivari died a natural death. It seemed Grierson did not hate Indians enough to sustain the campaign. Moreover, Sir Henry Cotton chose to write about the scandalous ownership of the magazine only after Temple died.

With so much pointing to Sir Richard Temple as the man behind The Indian Charivari, it is hard to conclude otherwise. Yet it is hard to believe that one of the highest-ranking civil servants of the British Crown in Imperial India could run a comic magazine by using a mercenary British soldier as a front, to foment racism, to spread hatred and to create a divide. Or is it really all that incredible?

Well, for all its comic candour relished by the gentry, who would have thought that hidden between the covers of The Indian Charivari was its greatest irony – a decorated British civil servant petrified that his dirty secret would be revealed.

– ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Devasis Chattopadhyay is the author of Without Prejudice, a corporate reputation and brand management strategist, and a columnist.