Lifting the Veil on Early Tamilakam (600-300 BCE)

BOOKMARK

It is through some facts and many legends that we first hear of what lay beyond the thick forests, deep in India’s south. The earliest historic, written reference to the kingdoms in the south comes from the 2nd and 13th rock edicts of Ashoka (274-237 BCE) where there is a reference to the Cholas, Pandyas, Keralaputras and Satyaputras who ruled the region. The vast corpus of Sangam literature, said to be the outpouring of the 3rd great Sangam or meeting of poets, in Madurai, around the 3rd century BCE also talks at length about the vibrant life during the early Pandya kingdom.

Based on all this, for the longest time, it was believed that the beginning of the early historic period - i.e. a period of urban expansion backed by the liberal use of iron, in the south started around 300 BCE. The region was seen as a bit of a late bloomer - compared to the North that had rapidly urbanised by then.

This long-held theory has gradually been debunked after the discovery of a series of sites that indicate that the broad region of Tamilakam - comprising Tamil Nadu, Puducherry, Kerala, South Karnataka and South Andhra more than kept pace with the progress in the North. At Adichanallur in the Thoothukudi district of Tamil Nadu, an excavation site close to Korkai, the old capital of the Pandyas, archaeologists, for instance, have found a settlement that was a mining town, which housed a diverse set of people between 905-696 BCE. Further excavations have taken this site back to 2500-2200 BCE.

In a 100-acre coconut grove, 12 km from Madurai, in Keeladi, even more stark evidence has been found over the last few years. Excavations have revealed what looks like a fairly large urban centre that was an important link in the east-west trade route. The wide range of over 1000 artefacts found here, over the last five years shows the evolution of local art, the urban spread, transformation of language and most importantly, the fact that this was a vibrant, affluent city, teeming with culture and life, way back in 600 BCE.

Archaeologists and historians are now beginning to piece together the complex jigsaw puzzle, which is the story of the early historic South.

The Vaigai River

As far as rivers go it is not the most well-known or the longest -- The Vaigai originates at the Western Ghats and runs through the Varucanadu hills and through the districts of Theni, Madurai, Sivagangai, and Ramanathapuram. According to legend, the Vaigai is the Ganga that descended from Shiva’s locks to quench the thirst of Gundotharan, one of Shiva’s companions or ganas. Many, even today, refer to the Vaigai as Shiva Ganga.

The Vaigai is historic. In fact, archaeologist P Balamurugan says this river played a significant role in the culture of Tamil Nadu and in the development of settlements. Hugging the length of the Vaigai, you will find sites that virtually tell you the story of man, in this region. Settlements found here range from Palaeolithic sites, to those from the late historical period. In fact, the entire river valley is dotted with archaeological sites Palaeolithic and Microlithic tools, rock art, and Iron Age graves. Over time, great towns and cities grew along the river’s banks. Historians believe that the Vaigai valley head-reach was the highway for the spices grown in the western ghats, to be taken to towns in the east, through millennia.

In fact Madurai one of the great cities along the Vaigai probably also has had continuous settlements from prehistoric times. The father of Indian prehistory Robert Bruce Foote found paleolithic tools close to Madurai, the most famous being the one from Aviyur. Subsequent excavations have revealed as many as 60 prehistoric sites just in the Madurai district!

Archaeologist Dr V Selvakumar, who teaches at the Tamil University in Thanjavur has done extensive work on the pre and early history of Tamil Nadu. He believes it is better to look at a more ‘recent’ past to understand the cultural continuity of the region. He says “We have a fairly clear picture of continuous human occupation in South India at least from 10,000 BCE. However, the developments become clearer and more complex from 3000 BCE with the beginning of animal domestication and agriculture.” This falls into the Mesolithic era in the South. While several archaeological sites - mainly megalithic burials from this era have been identified in South India, Selvakumar believes that a lot more work needs to be done on this because the link runs deep “There is a clear line of a genetic connection between people then and now, in the south. Their genes and their descendants exist among the populations in South India even today.” This Selvakumar tells us, is a further indication of the indigenous evolution of societies from hunter-gatherers to early agriculturists and finally urban dwellers, in this region.

Despite this prolific evidence of life, along the Vaigai, the earliest evidence of an advanced iron age period has come only recently, from Keeladi. This has created National headlines and major excitement in the History universe.

Why Keeladi is significant?

In its report ‘Keeladi - An Urban Settlement of the Sangam Age’, the Tamil Nadu Department of Archaeology sums up the significance of the work done at Keeladi, when it says that the finds in this site have now forced historians to re-examine and re-assess the old view that the Age of Sangam, synonymous with high culture in the South, started around the 3rd BCE. Carbon samples available from Keeladi take back the date of Tamil-Brahmi, the script associated with the early Sangam works to 6th BCE. This means that by this time, there was a fairly advanced community living here. Evidence of vast brick walls in Keeladi also indicates that there would have been a fairly large urban settlement. This, in turn, debunks an earlier theory that the ‘Second Urbanisation’ observed in the Gangetic valley hadn’t happened in the south.

The over 1000 artefacts found at Keeladi, over 5 excavation seasons starting in 2014 have helped archaeologists also piece together what life was like, when this was a thriving city. And it was one for long - all the way to the 12th CE - almost 1700 years!

The city had 3 phases. The earliest Period I went back to the Iron Age (6th century BCE to 3rd century BCE). The second was Period II which marked the Early Historic Period (300 BCE to 4th/5th century CE); and Period III the Post Early Historic Period (4th-5th CE to 11th -12th CE)

What egged on the interest of archaeologists through the 5 seasons of excavations here was the rich repository of artefacts that they found. As many as 5800 antiquities were unearthed in the initial years and these include myriad objects like glass and even gold beads, material indicating an advanced knowledge of weaving and dyeing, spearheads, elaborate brick structures, paved brick floors, grooved roof tiles, terracotta ring wells and rouletted ware and potsherds inscribed in Tamil-Brahmi. Many of these inscriptions appear with names similar to those found in Jain caves in the Madurai region and could date from the 2nd century BCE- 1st century CE.

The first few seasons clearly indicated that Keeladi was an important settlement that perhaps had trade links with Sri Lanka as well as internal trade with many parts of India. Since the settlement yielded complex structures archaeologists concluded that this could have been an industrial settlement.

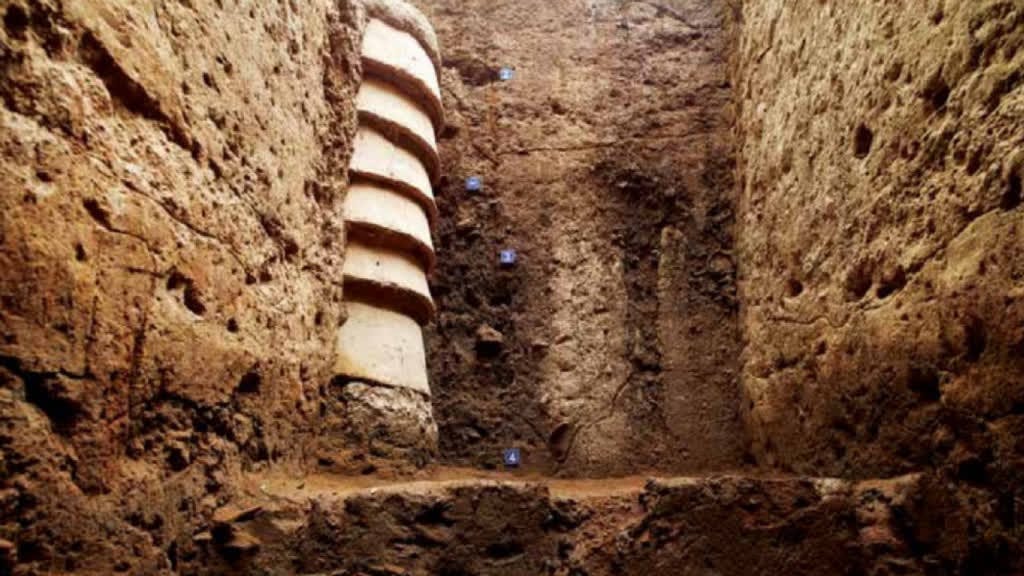

As they dug deeper, they found a lot more. An even higher number of antiquities were found during the period of 2017-18 and these included a large brick structure with a 16-metre-long wall and water-channel like structures, and also a terracotta pipeline which was in all probability a drain. By now it was clear that this had been a site of a fairly large and advanced urban centre even before.

A Harappan Link?

There was another discovery in Keeladi, that has opened up a whole new debate. During excavations, archaeologists found six hundred potsherds with archaic ‘graffiti like’ etchings. In all over 1000 graffiti potsherds were found to date during the five seasons. Symbols here included the likes of a ladder, fish, spirals, trident, sun and a single or double ‘u’ symbol.- found in many megalithic sites. These were possibly from even earlier and this buoyed interest, especially because some historians claimed that this could have been a link to the Harappan Script - which is yet to be deciphered. This, in turn, led others to say that the ‘Civilization in Keeladi’ may have been an offshoot of the Harappans!

Were the people here descendants of the Harappans?

Given that neither the graffiti nor the Harappan script has been deciphered and the fact that the resemblance is superficial at best - this is difficult to prove. In fact evidence here, on this question really runs thin. As Selvakumar explains there is a huge time gap between the end of the Harappan civilization, between 2000 and 1750 BCE and sites like Keeladi. As Selvakumar says, “Both these ‘scripts’ have to be seen in two different Spatio-temporal contexts”.

Selvakumar adds that our very idea of ‘civilisation’ needs to be re-looked at in the subcontinent’s context, “The concepts of civilisation and tribes have many interpretations. In India there existed many cultures and population groups from the early times, even coinciding with the Harappan Civilisation.” This is a fact if you see the various chalcolithic cultures that coincided even during the Harappan age, across the Indian subcontinent.

While the jury is still out on whether there is any connection between Keeladi and the Harappans. The fact is that we have a long way to go to fully understand this period in the South’s history. While there is growing evidence that gives us a tantalising peek into the lives of the people of Keeladi from the basic games they played like dice and hopscotch - over 600 hopscotches were excavated and terracotta discs with holes meant that they were used in toy carts or as twist disc game pieces or the gold artefacts they adorned themselves with - pendant, beads and rings, we still know very little. The plethora of sites across the Vaigai, Tamil Nadu and in fact the entire region, are yet to be properly excavated. There is little money to fund these projects and it is anyways complex because many of the cities and villages have been built and rebuilt over ancient sites. One of the main reasons for the breakthrough at Keeladi is that the site was not reoccupied in the Medieval period, or even today and this has protected the Early Historic layers, buried deep within.

As we wait for the Vaigai and ancient Tamilakam, to reveal its many secrets, we can for now, lean on literature, legends and the writings of the early Greeks and Romans to fill in some of the gaps in our understanding of this period of India’s history.

All photos courtesy: Dept. of Archaeology, Government of Tamil Nadu

This article is part of our 'The History of India’ series, where we focus on bringing alive the many interesting events, ideas, people and pivots that shaped us and the Indian subcontinent. Dipping into a vast array of material - archaeological data, historical research and contemporary literary records, we seek to understand the many layers that make us.

This series is brought to you with the support of Mr K K Nohria, former Chairman of Crompton Greaves, who shares our passion for history and joins us on our quest to understand India and how the subcontinent evolved, in the context of a changing world.