Bengal’s First Literary Awards

BOOKMARK

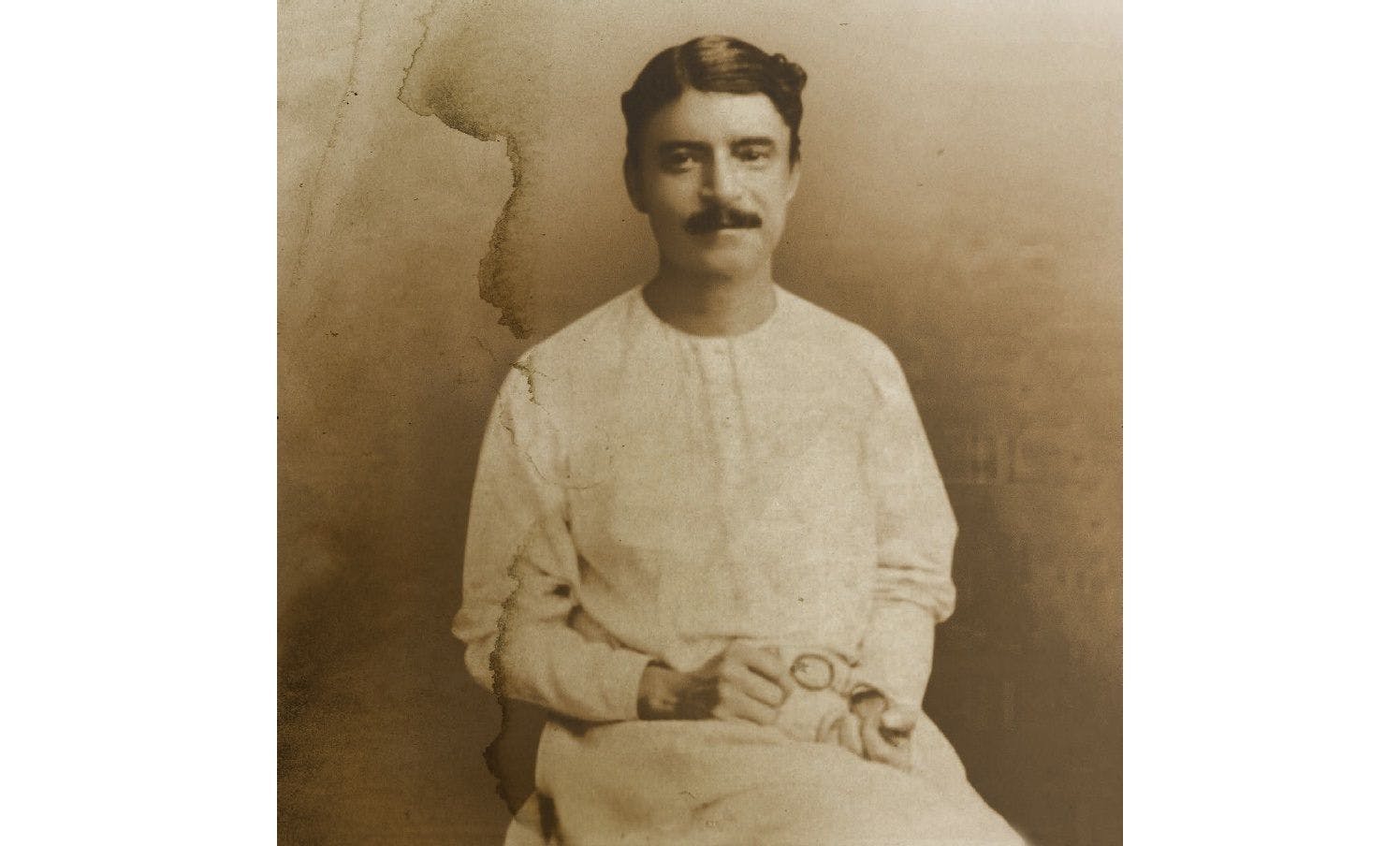

Hemendra Mohan Basu was a unique man. A gifted entrepreneur driven by eclectic tastes, Basu owned a perfume manufacturing business, a printing press and a publishing house, the first Indian bicycle works, a motor car company, the first gramophone-record manufacturing company in India, and was a pioneer of colour photography in the country.

But Basu is remembered, not so much by Bengal’s business community but in literary circles as the founder of the first literary awards in Bengal. Named after the perfumed hair oil he manufactured – and set up as an advertising tool – the ‘Kuntaline Awards’ grew in stature and were soon recognized by literary giants as well as budding writers in late 19th century Bengal.

– They are also among the first recorded literary awards in the country.

Basu, popularly known as H Bose, was a canny yet quirky entrepreneur, whose businesses were built on cutting-edge scientific advancements of the time.

Historian Michael Kinnear, in his book ‘The Gramaphone Company's First Indian recordings, 1899-1908’ (1994), writes that Hemendra Mohan Basu was born in 1864 in the village of Jaysiddhi, in Mymensingh District of Bengal (in present-day Bangladesh). After completing his schooling, he took admission to the Medical College in Calcutta but abandoned his medical career when a freak lab accident caused damaged to his eyesight.

Only 26 years old at the time, the youngster was brimming with ideas, and he thought life was just too interesting to waste on a routine job. Basu chose to become an entrepreneur instead and began manufacturing hair oil in 1890. The first product he launched from his factory at 24, Musalmanpara Lane was ‘Kuntaline’ (‘kuntal’ means ‘hair’ in Bengali) hair oil, and he soon rolled out other products including the popular Delkhosh perfume, Tambuline paan masala and several fruit syrups.

Later, Basu moved into a home at 5 Sibnarayan Das Lane and shifted his factory to 62 Bowbazar Street. When he finally bought a house at 52 Amherst Street, Basu used the premises at 5 Shibnarayan Das Lane for his printing and publications division, known as Kuntaline Press. Several issues of the renowned magazine Prabasi rolled out of this press.

A successful businessman by now, Basu realised the importance of branding his products. Although the products of his competitors such as Jabakusum and Keshranjan hair oil eventually outlived his Kuntaline brand, it was Basu’s advertising methods that set his products apart. This included advertising in newspapers and magazines owned by Bengalis like Prabasi and the Amritabazar Patrika.

Chandak Sengupta mentions in his book The Rays Before Satyajit: Creativity and Modernity in Colonial India:

“There were no gods, goddesses or avatars in his advertisements, and the human figures were mostly Indian, especially women with long and luxuriant hair or ‘real’ people like nationalists Surendranath Banerjea and Lala Lajpat Rai, or iconic celebrities like Rabindranath Tagore. Bose’s advertisements were full of striking illustrations by Bose’s eldest son Hitendramohan (1893-1963) and painter Purnachandra Ghosh (1885-1949), who had turned to commercial art to make a living.”

Sadly, not much remains of these advertisements except reproductions in old newspapers owned by collectors, who sometimes put them on display. Basu also experimented with other forms of advertising like posters in tramcars.

It seemed Basu enjoyed promoting his hair oil as much as he loved making it, and he never stopped innovating with advertising techniques. While his competitors used testimonials in their advertisements, Basu came up with a jingle that is still popular among people interested in Bengali literature. It went like this: ‘Kesha Makho Kuntaline/ Rumaletey Delkhosh, Paney Khao Tambulin, Dhonno Hok H Bose’ (‘Apply Kuntaline to your hair, Delkhosh in your handkerchief, Tambulin in your betel and bring fulfillment to H Bose’).

Another winning idea hinged on the swadeshi nature of Basu’s Kuntaline hair oil and even bordered on emotional blackmail. In his advertisements, Basu accused those who used foreign products as ‘lacking self-respect’.

Although many of his advertising strategies were new for the times, launching a magazine titled Kuntaline was a masterstroke. He not only played on the literary bent of educated Bengalis to market his perfumed hair oil but also used product placement to market it!

– Using cash prizes as incentives, Basu invited writers across Bengal to contribute to his magazine.

But there was one condition – contributors would have to use the terms ‘Kuntaline’ hair oil or ‘Delkhosh’ perfume in their stories without making it look like an advertisement. For the late 19th century, this was a stroke of marketing genius.

The first Kuntaline Awards were announced in 1896, and Basu, once again, used the nationalist plank as a yardstick for the winning stories, which was totally in sync with the Swadeshi Movement of that period. Stories that were copied or inspired by foreign writers were instantly disqualified even if they were well written. On the contrary, stories with unique plots and no foreign influences would be entertained, even if they were not well written.

In the early 20th century, the Kuntaline Awards became very popular among educated Bengalis. Many writers, who later became legends, had their stories published in Kuntaline magazine. Basu also published a separate book with the prize-winning entries every year. This ensured that all his products, especially Kuntaline, became household names.

– The first Kuntaline Awards gave out its first prize of Rs 50 to Jagadish Chandra Bose in 1896.

Bose, a scientist, polymath and writer, wrote anonymously in the magazine like many other authors who preferred to use pseudonyms. Titled Nirrudesher Kahini (Story of the Untraceable), Bose’s entry is regarded as the first science fiction story in the Bengali language. It is a story of a massive cyclone that threatens to destroy Calcutta. As the people fear the worst, the cyclone mysteriously disappears suddenly without a trace. The answer is only known to the Kuntaline Hair Oil using Hero of the story, who is on a ship to Ceylon. The story goes that as the ship faces huge cyclonic waves that threaten to overwhelm it, the hero desperate to save himself remembers reading a scientific study of how oil floats above the water and in desperation throws his stock of Kuntaline Hair oil into the see. Suddenly, the Cyclone disappears and the hero is saved. While the story seems quite farfetched, JC Bose did republish an updated version of the story in 1921.

Many other eminent writers too contributed to the magazine. The next year, the first prize was awarded to novelists Prabhat Kumar Mukhopdahyay, who wrote under the female pseudonym ‘Radhamoni Devi’. Not only famous novelists but upcoming writers also bagged Kuntaline awards. Famous novelist Sarat Chandra Chatterjee had his first-ever story published in Kuntaline. Published under a pseudonym in 1902, his story was titled Mandir (Temple).

In 1903, Basu published a special issue of Kuntaline, which carried only one story. Titled Karmafal, the story was penned by Rabindranath Tagore. The issue also carried paintings by Purnachandra Ghosh.

Although the stories published in Kuntaline magazine were compiled and published as collections of stories between 1989 and 1996, it is almost impossible to get hold of an original copy of Kuntaline magazine today.

If the Kuntaline brand was Basu’s most high-profile achievement, he was an entrepreneur in other pioneering businesses as well. In 1900, he established the Great Eastern Motor Co. and set up a car repairing unit called the Great Eastern Motor Works, located in Park Street, Calcutta. He imported cycles and established India’s first Indian-owned cycle company H. Bose & Co. — Cycles at with showroom at 63-1, Harrison Road, Calcutta. He was also one of the early pioneers of colour photography in India, using Autochrome Lumière slides for his photographs.

Hemendra Mohan Basu is also called the ‘Father of Indian Sound Recording’. He procured Edison’s phonograph in 1900 and made voice recordings of close friends and relatives. He opened the ‘Talking Machine Hall’ at Dharamtolla Street (now Lenin Sarani), where anybody could record their voice. His first advertisement on the phonograph was published on the 16th of February 1906.

In fact, Rabindranath Tagore had several of his recordings done on cylinder records, and, during the Bengal Partition in 1905, Basu recorded many political speeches and songs on this device. Rabindranath’s son Rathindranath in his book Pitrismriti (My Father’s Memories) writes of the close relationship between Rabindranath Tagore and Hemendra Mohan Basu. Sadly, almost none of these extremely valuable recordings survive today.

Hemendra Mohan Basu died on the 26th of August 1916 after a tooth infection. His house still stands, rather unceremoniously, at 52 Amherst Street. There is no plaque or statue to indicate that this was the home of the pioneering entrepreneur who launched the first literary awards for Bengali literature. Today, there are so many literary awards that tip their hat to talented writers but Kolkata, and the organizers of modern literary festivals, appear to have completely forgotten this trailblazer.

– ABOUT AUTHOR

Amitabha Gupta is a heritage enthusiast, travel writer, photographer and blogger who has been writing on the heritage of Eastern India for travel magazines and publications.