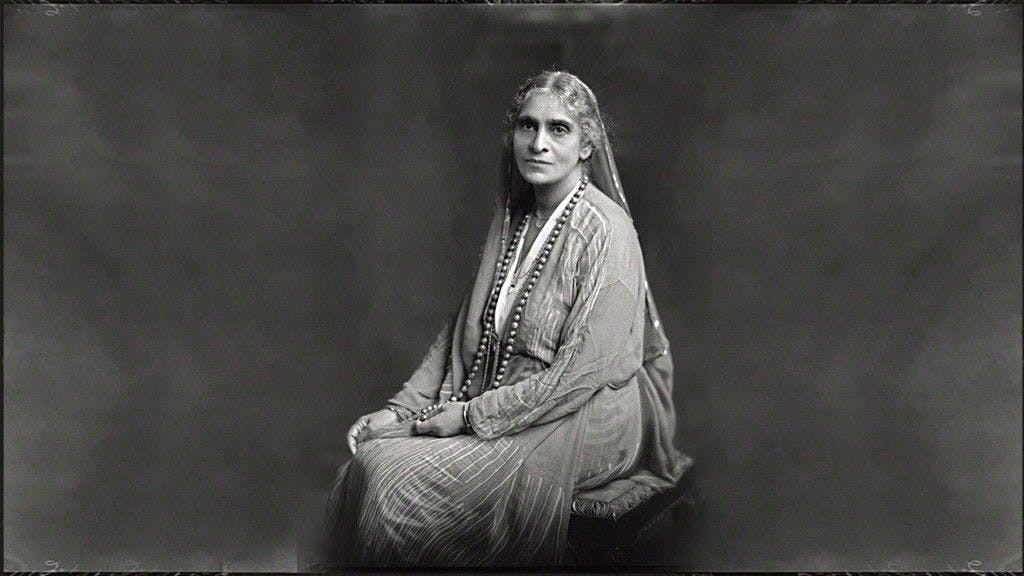

Cornelia’s Fight

BOOKMARK

There are few stories that can inspire you and frustrate you at the same time. The story of Cornelia Sorabji is one such. The first woman to matriculate from the Bombay University, the first Indian woman to graduate from a British university, the first woman lawyer of India. Cornelia Sorabji’s life was full of firsts but it was also full of hurdles as she took on patriarchy, like no one had done before. It is amazing how the world conspired to keep Cornelia out, and it's even more spectacular to see how she fought back!

In the late 19th century professional opportunities for women were very limited in Victorian England and India. Gender roles were sharply defined. Women did not have the right to vote or own property. They also couldn't pursue a career they wanted and earn a decent living.

Cornelia Sorabji was born on 15th November 1866 in Nasik. Fifth in a family of seven girls and one boy, her parents were advocates of education and women empowerment. Her mother held a respectable position in Poona where she founded four schools. While her father, Reverend Sorabji Karsedji who had converted to Christianity, also had to face social isolation from the Parsi community.

Cornelia’s father taught her up to the level of matriculation, but the University of Bombay (Mumbai) refused to allow her to sit for her matriculation exam as she was a woman. After much lobbying, she was allowed to join the Deccan college of Pune, to study English literature. As the only female among 300 male students, Cornelia faced a lot of hostility and pranks. Doors were actually slammed on her face at times when she went to attend lectures! Despite this, her brilliance shone through. Cornelia finished a five year Latin course in a single year and won the college scholarships every year. In 1887, she was the top student at Deccan college and one of just four students of the University of Bombay to get a first-class honours degree. She became the first woman to graduate from the University of Bombay.

As a University topper, Cornelia was eligible for a Government of India scholarship to study in England and she was really keen to study at Oxford. However, this scholarship was denied to her as she was a woman. Cornelia wrote to parliamentarians in England against this injustice and several prominent Britishers took up her cause. Some British women, led by Florence Nightingale, the founder of modern nursing, even put together funds in lieu of the scholarship, she did not get because she was a woman. With this financial assistance, Cornelia reached England on 19th September 1889.

But Cornelia faced a push back here too. While she had hoped to study law at Somerville College at Oxford, she was denied admission and asked to study English Literature instead as it was considered ‘more suitable’ for women. Cornelia had no choice but to study English Literature. However, her achievements had made her a mini-celebrity at Oxford. Among her friends was noted Sanskrit scholar, Max Muller. She also developed a close friendship with Benjamin Jowett, an administrator and a tutor at Oxford’s Balliol College. Jowett described her as ‘as the one who would interpret East and West to each other’ and lobbied hard with the Oxford University to allow her to study law.

Finally, in 1890, a special undergraduate course was devised for her so she would be able to answer the same examination papers in law, that candidates appearing for the Indian Civil Service were attempting. This concession worked and her exam results proved that her aptitude was above average. Cornelia was now free to study for Bachelor of Civil Law, which men generally took only after legal experience as barristers. In 1892, however, the external examiner refused to examine a woman’s exam papers. But Jowett had Oxford University's Council override him.

While pursuing her Bachelor's degree, Cornelia spent a year with a solicitors firm, Lee & Pemberton in Lincoln’s Inn Fields in London, becoming the first woman ever permitted to read in the Lincoln’s Inn Library. Although she passed her exams of ‘Bachelor in Civil Law’ in 1892, she was not awarded any degree, as Oxford did not confer degrees on women. It was only in 1922, thirty years after she had graduated that she was awarded her degree from Oxford.

Cornelia returned to India in 1893, but her struggles continued. The Chief Justice in Bombay, Sir Charles Sargent, instructed the solicitors not to employ a woman. He told her quite bluntly:

‘You see you are not a man, and no woman should be allowed to meddle with the law’.

This was just the start of her decades-long struggle to find a legal position in India. Despite lobbying hard, the British government especially Lord Curzon, the Viceroy of India, was totally opposed to giving her any legal position as he did not believe that women should be employed.

In 1895, Cornelia decided to write the LLB exams at Bombay University, because successful candidates in these exams were automatically entitled to be admitted to the Indian bar. However, when she passed the LLB exams in late 1896 and sought formal admission to the bar, her applications were denied, and the reasons were the same. All her degrees and education meant nothing because she was a woman!

While Cornelia faced successive obstacles in India, her brother Dick, had qualified as a barrister in London (in the same batch as Muhammad Ali Jinnah). The brother-sister duo moved to Allahabad, which was then a premier law court in India with legal luminaries like Motilal Nehru and Tej Bahadur Sapru, practicing there. Cornelia had nursed hopes of working at the Allahabad High court, but her hopes were dashed, once again, when the British Chief Justice of Allahabad High Court used his casting vote to disallow her. He remarked to her in ‘jest’ -

‘ If you appeared before me, how could I scold you?’

With little options left, Cornelia did the next best thing. She became a lawyer for the Maharajas, who were less hostile to women than the British establishment. This, however, was of no help, as Maharajas often allotted absurd cases to her – one was defending an elephant against somebody who had removed its favourite banana grove!

By 1899, Cornelia had spent five years trying to become a barrister. She needed to change her stance and so she invented her own job description outside the legal setup as legal advisor to Purdahnashins or ‘women in purdah’. These were women from the Zamindari or noble families who were in strict purdah and not allowed to interact with men, except from behind a curtain.

Many of these women had been married off in early childhood and since then, based on religious and cultural beliefs, had been in purdah. On becoming widows, they were by default in charge of the large properties their husbands left behind. As the women were uneducated and lived in absolute seclusion, people often tried to get their money through fraudulent ways.

Cornelia was the only person who could interact with them and fight their cases. As their legal advisor and as a woman, Cornelia was in a unique position to help them. She was a great success at it and over the first 18 years of her career, till she was 54, she continued to help these women.

Besides exercising her expertise in inheritance, adoption and dispute resolution, Cornelia also put in efforts to make their lives better. She held ‘Purdah parties’ so that these women had a chance to get out of their homes and socialize with other women. She appointed tutors for the children so that the next generation would be educated and looked after their health.

Finally, this role which Cornelia had created for herself got official approval from the Government in 1904, when the government appointed her as Lady Assistant to the Court of Wards, a Government body that looked after the properties of minor children.

From 1904 to 1922, Cornelia worked at her office in Writers Building in Calcutta and had some hair raising adventures travelling to remote areas of Bengal, Bihar and Odisha, which she penned down in her books Love and Life behind the Purdah and The Purdahnashin.

In 1922, she was called to join the Bar at Lincon’s Inn in London which had been opened to women the previous year. The same year, 30 years after, she collected her degree from Somerville College, Oxford.

When the legal profession was opened to women in India in 1924, Cornelia set up a practice in Calcutta. Predictably, this was not the end of her fight, as, although men did not mind taking the guidance of a woman, they certainly would not stand being defeated by one in the courtroom. Therefore, she was confined to the aspect of only preparing cases and never arguing them before a judge.

As a social worker, she was associated with the National Council of Women in India and started the Bengal League of Social Service for Women. In 1926, she carried out a campaign against infanticide. But Cornelia faced a lot of problems due to her opposition to Gandhi. Cornelia had been a friend of moderate congress leaders like Gopal Krishna Gokhale and disapproved of the civil disobedience espoused by Gandhi. Richard Sorabji, Cornelia’s nephew and biographer, believes that it was due to her opposition to Gandhi, that Cornelia burnt so many bridges in India.

Cornelia retired from her legal career in 1929, and settled in London, visiting India during the winters. She also wrote two autobiographical works titled India Calling (1934) and India Recalled (1936). She died at her London home on 6 July 1954.

On 15th November 2016, to commemorate the 150th anniversary of Cornelia Sorabji’s birth, her alma mater, the Somerville college at Oxford introduced the Cornelia Sorabji Scholarship for Indian students wanting to study law there.

Cornelia Sorabji was a trailblazer who smashed through an unbelievably high glass ceiling to leave her mark. She did this with a rare combination of passion, courage, determination and patience. Today, as women in India lead the charge at courts and corner offices, boardrooms and cricket fields it is time to remember and thank women like Cornelia Sorabji who made it all possible!

Cover Image: National Portrait Gallery, London