Jallianwala’s Widows: Standing Tall

BOOKMARK

On April 13, 1919, the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre changed the course of the Indian freedom struggle. This premeditated, cold-blooded mass killing of 500-odd men and women in Amritsar prompted Mahatma Gandhi to launch the Non-Cooperation Movement, thus upping the ante against the British in the struggle for Indian independence.

The history books tell us of the cavalier manner in which Brigadier-General Reginald Dyer ordered his men to open fire on the crowd that had assembled to celebrate Baisakhi and to also register a peaceful protest at the Jallianwala Bagh. They tell us how Dyer and his troops, from a vantage point, directed their bullets at the gates of the Bagh so that no one could escape. They tell us that the troops fired till their ammunition was exhausted and left a bloodbath and piles of corpses in their wake.

What the history books don’t tell us are the stories of incredible courage, utter anguish, and quiet defiance that surround this monumental event. Among these are the stories of two women, who registered their protest against the British government in India by rejecting any support that was extended to the families of the massacred victims.

This is the story of Attar Kaur and Rattan Devi, who lost their husbands in the bloodbath at the Bagh and who, by standing up to the colonial government, preserved the honour of not only their husbands’ sacrifice but of all those who were killed in the bloodshed.

‘Blood Money’

The Jallianwala Bagh massacre brought considerable disgrace to the British in India and drew scathing criticism from intellectuals, Indian leaders as well as the English people back home. Thus, as a measure of damage-control, the British offered the victims’ families an inducement to ‘forget’ the incident; they offered monetary compensation.

The distribution of compensation began on June 15, 1921. Noted Indian historian Vishwa Nath Datta wrote in his book Jallianwala Bagh Massacre (1969; later reprinted in 2000) that along with the families of those who had perished, individuals who had suffered economic harm due to the incident too were compensated.

But there were two women who could be neither mollified nor muffled. The compensation was distributed according to the economic conditions and the extent of the damage occurred. Accordingly, Rs. 25,000 was offered for the life loss to Attar Kaur and Rattan Devi, the widows of Bhagmal Bhatia and Chhaju Bhagat, but for them, this wasn’t about money. They rejected the compensation outright, saying they wouldn’t accept any help from their husbands’ murderers. It would be a crime to accept ‘blood money’ in lieu of their murdered husbands, they reasoned.

P N Chopra, in his biographical journal on freedom fighters, Who's Who of Indian Martyrs (1969), mentions that after General Reginald Dyer and his soldiers left the scene of the massacre, a pregnant Attar Kaur entered the Bagh to collect the body of her husband. With the help of a neighbour, Santa Mishra, she carried the corpse home.

Their family was living in Amritsar’s Mohan Nagar neighbourhood, and their eldest son Mohan Lal was too young to carry forward the family’s timber-wood selling business. They were devoid of a means of livelihood. Attar Kaur had no choice but to do household chores to run the family.

After independence in 1947, the then President of India, Dr Rajendra Prasad, compared Attar Kaur’s younger son Sohan Lal, who was born seven months after the massacre on November 20, 1919; to the legendary character of ‘Abhimanyu’. Not only he, even President Giani Zail Singh and Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and Indira Gandhi honored him, and still, neither the family ever asked nor did they receive any financial assistance from the government. Later, Attar Kaur died on January 31, 1964.

When Sohan Lal grew up, he opened an electrical appliances store in the Sultanwind Road neighborhood in Amritsar but his shop was burnt to the ground during the insurgency in Punjab in the 1980s. His only recourse was to take up a blue-collar job to sustain his family but he couldn’t bear the indignity in the city where his mother had earned so much respect. Sohan Lal and his family thus migrated to Delhi, where he died at an age of 92 on July 13, 2011. Today, his son Ravi Bharti lives in the Uttam Nagar neighborhood of Delhi.

Night Without End

Like Attar Kaur, Rattan Devi had a similar story of pain and suffering, which she told the Jallianwala Bagh National Memorial Trust that controls the Bagh and its activities. According to her, when the first bullets rang out at the Bagh, she was at home, nearby. When she heard the shots, she grew worried as she knew her husband was in the Bagh.

She rushed to the site along with two other women and her worst fears were confirmed. Rattan Devi just stared at her husband’s body, which just lay there, amid a pile of other blood-stained corpses. She said in her account to the Trust, “After some time, both sons of Lala Sundar Das (a neighbour) reached there. But I sent them back to bring a charpai (woven bed) to carry my husband’s corpse; soon I sent the ladies too. I just stood there waiting for them and sobbing. Soon it turned eight at night and curfew was imposed all over, as a result of which no one would come out of their houses.”

Then a young Sikh boy appeared from nowhere and Rattan Devi asked him for help. It has never been officially confirmed but it is a popular belief that the boy was Sardar Udham Singh, the man who years later, in 1934, killed Michael O'Dwyer, who was the Lieutenant-Governor of Punjab during the Rowlatt Act and Jallianwala Bagh massacre.

– The assassination was meant to avenge the various atrocities in Punjab that happened in 1919.

Since the ground was drenched in blood and there were corpses everywhere, Rattan Devi with the boy’s help took her husband’s body to a dry place, where she placed it on a wooden plank. After the boy departed, she waited till 10 pm but still no one came. It was just her, a smattering of injured people and corpses all over.

Leaving her husband’s body behind to get some help, Rattan Devi went to the nearby Katra Ahluwalia neighbourhood. But her requests for help to transport her husband’s corpse were turned down by the men in the locality. She reached the market, where she found an old man smoking a hookah and a few others sleeping in the vicinity. She begged the old man to help her. Although he was willing to go with her, the others weren’t, saying they did not want to pay with their lives for violating the curfew.

Hopeless, Rattan Devi turned back. She told the Trust-

“Besides the body of my husband, there were three other men groaning with the pain of their severe injuries. A buffalo was also in pain as she had been shot. A 12-year-old child too was requesting me not to go but I said I wouldn’t go anywhere leaving my husband’s corpse. I asked the child if he was cold and whether I should put my blanket over him. But he asked for water instead, which wasn’t possible to find at that time. At that very moment, I found a bamboo cane, which I kept in my hand to hush off dogs who had gathered to nip and tear the flesh.”

The clock tower outside Sri Harimandir Sahib counted the hours as it chimed on the hour, every hour. At 12 am, Rattan Devi found a man from Sultanwind village who had been trapped in the wall at the Bagh. He requested her to help him, so Rattan Devi freed him by pulling at his clothes. Finally, at six in the morning, her neighbour Lala Sundar Das, his son, and some other neighbours brought a charpai and took her husband’s body home. In the Bagh, there were other people also searching for their relatives.

While concluding her statement, Rattan Devi said, “It was difficult to describe what all happened to me that night in the Bagh. Whereas some were lying on their backs, others were by their face. There were also many innocent children.” As Ratan Kaur died without an issue and didn’t have a family in the city apart from her deceased husband, we don’t have any information about her later life and death.

An Englishwoman’s Protest

Actually, Attar Kaur and Rattan Devi were not the only two women who refused compensation; there was another woman who protested against the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in the same way. She had a peculiar story as she had neither lost anyone in the bloodbath, nor was she Indian. She was an English missionary named Marcella Sherwood, the manager of City Mission School, who worked for the Church of England’s Zenana Missionary Society in Amritsar.

Sherwood was returning home on her bicycle on April 10, 1919, when she was attacked by a local mob that was enraged by the police attack of the day before, in which 24 Indians were killed. The people were smouldering with anger against the British government and had been attacking any English people who crossed their path.

Sherwood was beaten and left for dead. Later, a local Indian doctor, whose son had been a student in her school, rescued her and bandaged her wounds. Despite the near-fatal attack, she severely criticised the British government for its atrocities on the Indian people.

The protests by Attar Kaur, Rattan Devi and Marcella Sherwood were not dramatic nor did they draw much attention. They are mere footnotes in an event remembered more for its brutality than the courage that prompted women like these to stand up to their colonial masters.

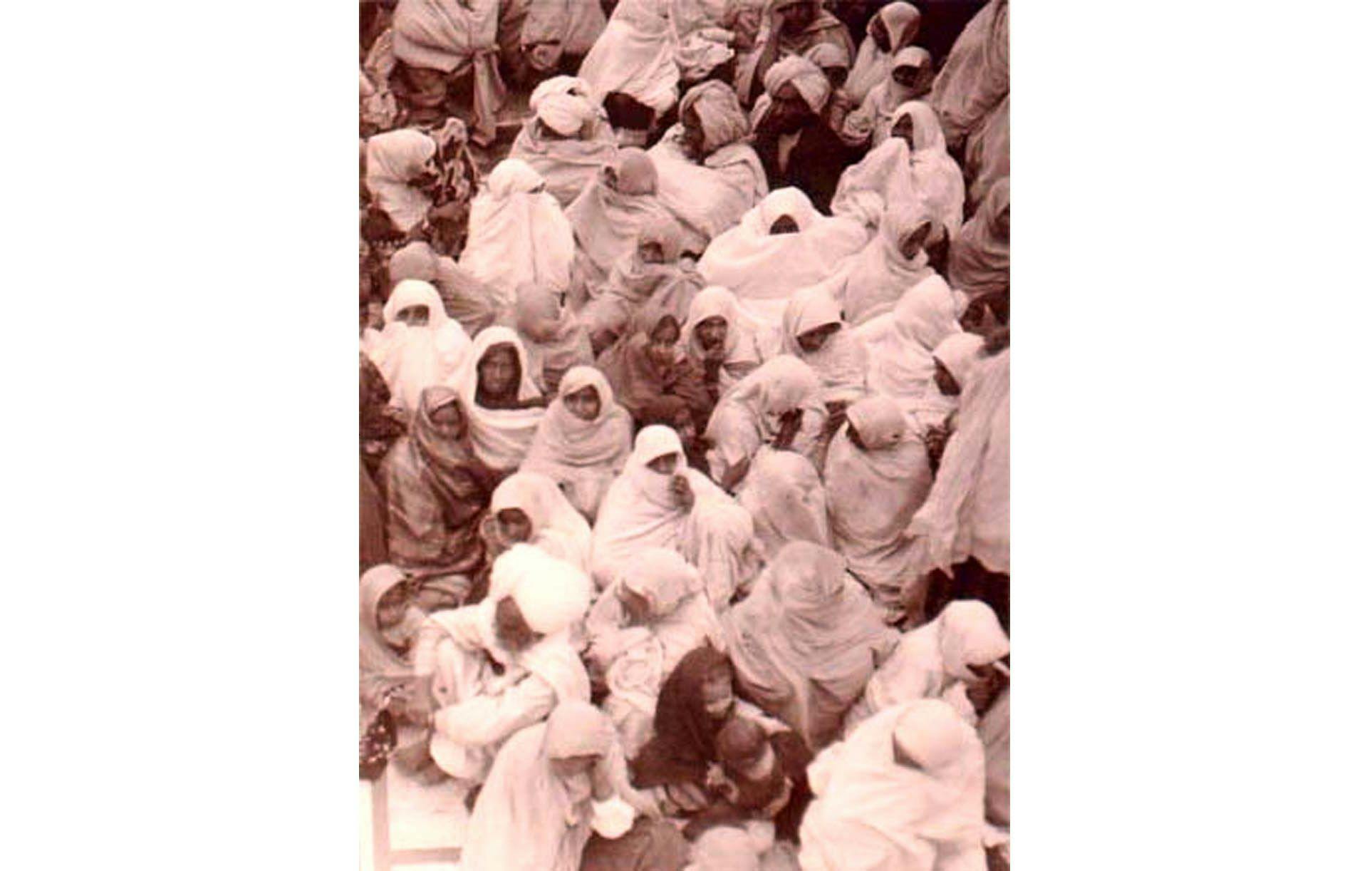

Cover Image: Families of killed mourning the day after incident (Courtesy: Aashish Kochhar)

Jallianwala Bagh: Lifting the Veil