The Elusive Kalabhras (3rd CE – 6th CE)

BOOKMARK

On a cold winter day, some time in 406 CE, groups of Germanic tribes – barbarians to the chroniclers of the Roman Empire – made their way down the Rhine. They were the Vandals, Suebians and Alans from further afield. The event, called the ‘Crossing of the Rhine’, was important because these tribes used the frozen river to make their way down and breach the boundaries of the Roman Empire. Already in deep decline thanks to political turmoil, economic drain and earlier Gothic inroads made as the Huns swept into Europe, these latest waves of invasions from the north sounded the end of the once great Roman Empire.

This event has been well chronicled and you can find mention of the Gothic invasions even in school textbooks in India. Ironically, it was this reference that I remembered when I was studying a similar ‘wave’ that swept by closer home, in India, 200 years before, in the 3rd CE. These were waves of ‘invaders’, the Kalabhras, who made their way from beyond the northern boundaries of Tamilakam – the area covering modern-day Tamil Nadu and Kerala – to take over the once-prosperous city of Madurai. These invaders defeated a succession of princes from the ruling dynasties of the South, the Sangam-era Cholas, Cheras and Pandyas, who had dominated the land for centuries. And, for the next 300 years we are told, it was as though a veil had fallen over the region.

Sadly, we know very little of the Kalabhras.

For a long time, this period of the Kalabhras was described as the ‘Dark Ages’ in the history of Tamilakam. They were painted as villains in accounts, and later even dismissed as insignificant non- entities who left no trace of themselves. So little was known about this period of roughly 300 years between the 3rd CE and 6th CE that it was clubbed and brushed aside as the ‘Kalabhra Interregnum'.

Villains, marauders or just victims because they were on the wrong side of history and faith? Over the decades, based on literary records, epigraphic material and painstaking research, the veil is just about lifting from the Kalabhras. This is an attempt to piece together their story, from what we know of them, so far.

To understand the Kalabhras, you have to understand the early history of the region that comprises modern-day Karnataka, a region with a fascinating past.

The Wealth Beneath

A 90-minute drive from India’s IT hub Bengaluru is a hill that is quite a wonder. Just 1,478 m above sea level, the greatness of Nandi Hills doesn't lie in its height – even though it’s the tallest peak in the region. It lies in its historic value. It is well known that this protrusion (the hill) is part of the very bedrock – the building blocks of the Indian subcontinent – a part of the 3.5-billion-year-old Dharwar Craton, one of the oldest land forms on the earth. The sheer age of this area and the region – it is the oldest part of the Peninsula – ensures that this area sits on great mineral reserves.

While the political, economic and cultural rise of Tamilakam owed a lot to its vibrant ports that acted as conduits of trade across oceans, the region north – covering present-day Karnataka – rose because of this wealth it sat on – iron, gold and thick forests.

Stretching from Bidar in the North to Mysore in the South, from Mangalore on the coast of the Arabian Sea to Kolar on the border of Tamil Nadu (and many regions in the middle, criss-crossed by a series of rivers rising from the Western Ghats – the Tungabhadra, Kaveri and Pennar), few states in India reflect the geographical or cultural range and spread of Karnataka. Not surprisingly, the disparate regions that together form the state today, have birthed their own micro-cultures and histories.

But even as different kingdoms have risen and fallen during different times and along different stretches of what we today know as Karnataka, there are some threads that have held it together.

The Harappans, in all probability, sourced gold from the Kolar mines in South Karnataka, which continued to be a prolific supplier of gold till the 20th CE.

The series of Ashokan edicts, nearly all of which are in the mineral-rich districts of Karnataka in Koppal, Chitradurga, Brahmagiri, Raichur, Bellary and Gulbarga (Sannati), indicate that this iron ore-rich area was well within Mauryan dominion. This was also an area – stretching down to Mysore (then called Kuntala) – that the Satavahanas held sway over till the 3rd CE.

Rich in minerals and forest wealth, this area was important for the empire builders of the North and the kingdoms of the South.

Sangam Literature makes specific reference to the hills and forest tracts bordering Tamilakam, where the language was different. This, historians believe, refers to the region that stretches from mountains around Tirupati to Bengaluru and the large forest tracks covering the present-day region of Kolar. This area was an important source of wood, elephants and ivory, which was sourced from the local tribes and chiefdoms, probably the ancestors of the Kalabhras who lived here. Interestingly, Sangam Literature refers to Mysore as ‘Erumainadu’ or the ‘land of buffalos’ (erumai). Later, Mysore gets its name from the myth of the Buffalo King Mahishasura, who is slain by Goddess Durga.

Around the 3rd CE, as the Satavahana Empire weakened, as did the kingdoms of the South – the Sangam Chera, Chola and Pandyas – thanks in large part to the collapse of Roman trade, the area in between saw a period of flux. Old feudatories of the Satavahanas, the Ikshvakus, Mahabhojas and Pallavas, wrenched free and the tribes and clans on the edges, in the hills and forests bordering Tamilakam, ventured out.

Historians believe that it is from the hilly, forested stretch between Nandi Hills and the Chandragiri Hill (made famous as the place where the founder of the Mauryan Empire Chandragupta Maurya passed on), that the Kalabhras rose, around the 3rd CE. The Kalabhras, like Chandragupta Maurya, were followers of Jainism.

The Kalabhra Trail

‘Then a wicked king named Kalabhran took possession of the extensive earth driving away numberless chiefs’

Velvikudi Grants L 39

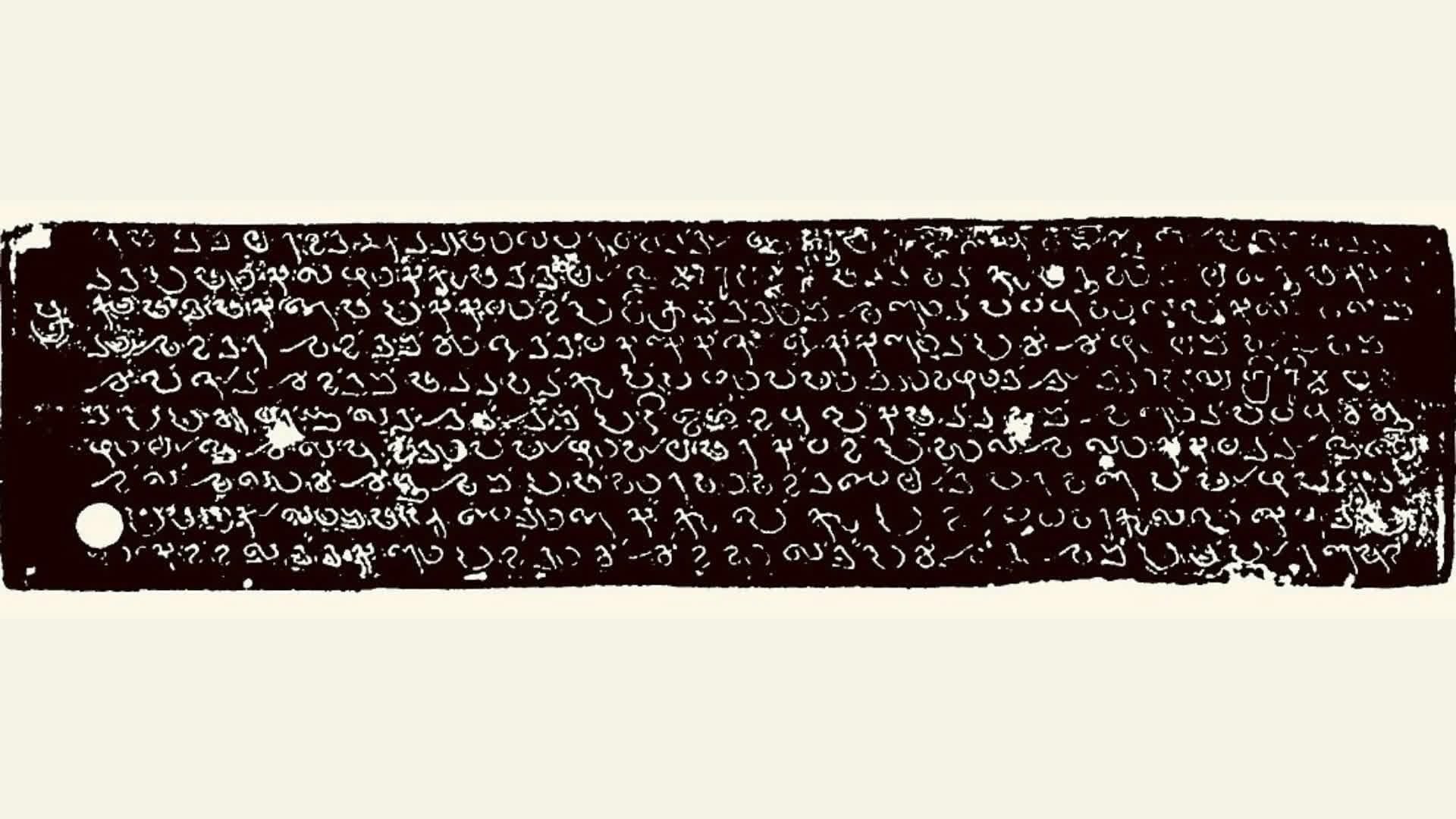

The most important milestone in piecing together the story of the Kalabhras was the discovery of the Velvikudi inscription, an 8th-century CE copper-plate grant from the Pandya kingdom of Southern India, found near Madurai in Madakulam, and currently housed in the British Museum in London. Inscribed in both Sanskrit in the Grantha script and the Tamil language, it records, among other things, the renewal of a grant of Velvikudi village to a Brahmana by the Pandya king Nedunjadaiyan. But it is the backstory to the renewal that makes this interesting.

According to the inscription, the village of Velvikudi, which had been given as a grant to the Brahmana by an earlier Pandyan king after he conducted a yajna (sacrifice) here, was overrun by a conceited and cruel ruler named Kalabhran, who seized the land and drove away ‘numberless’ princes. The inscription goes on to say that a Pandyadhiraja named Kadumkon, ‘Who, like the Sun rising from the vast sea’, won back the land. The long, 155-line inscription has two references to the Kalabhras – one in singular and the other in plural, leading historians to believe that the Kalabhra forces were banded under a chief who marched against the Pandyas.

There are other references to the Kalabhras but, interestingly, most of them date from the 6th to the 10th CE. These refer to how they had been ‘driven’ out by a Pandya, Pallava and even a Kadamba king from different parts. There is, for instance, a reference to the Pallava King Simhavishnu defeating Kalabhras in the 6th CE as he extended his rule south beyond Kanchi.

One reference that stands out, however, is the one cited by historian Dr S Krishna Swami Aiyangar in his book Ancient India Vol 1. He points to the “confirmation” of Kalabhra rule in the Chola country in the 5th CE through the writing of a monk Buddha Dutta, who was from the village of Boothamangalam and lived in Ceylon. He is said to have written a work in Kaveripatanam during the reign of a king named Achchutta Vivanta or Acchyuta Vikrama of the Kalamba dynasty. This, Aiyangar believes, is a probable reference to the Kalabhras.

Aiyangar goes on to point to similar references to some “Kalamba” chieftains having control over areas in and around Tanjore in later periods. This has made him conclude that “The Kalabhra migration must have taken place earlier than this – a few generations earlier (than Acchyuta Vikrama of the Kalamba Dynasty), for them to have achieved the conquest and dismemberment of the Chola kingdom”. He goes on to surmise that “the 5-7th CE may have been centuries of Kalabhra rule even though they may have been (later) reduced to chieftains who probably aligned with the Pallavas and the Pandyas in battles later”.

Theories of Origin

There is a hearty debate around where the Kalabhras actually came from.

Some early scholars believed that the Kalabhras were local followers of non-Vedic faiths who had risen against the tyranny of Brahmanical control. This is not a theory that has stood the test of time. Others dip into Sangam Literature to try and extrapolate the early history of the Kalabhras.

Interestingly, while there is no reference to Kalabhras in Sangam Poetry, a certain chieftain ‘Pulli of Venkatan', is referred to in a verse connected with Sangam era Palai or love poetry. In these verses, a mother of the heroine tries to describe the heat of the desert through which her daughter has eloped to the parched aridity of the Venkata hills ruled by Pulli Chief of the Kalvar. Some historians have opined that this Kalvar Pulli could have been a progenitor of the Kalabhra clan.

Efforts have also been made to trace the roots of the name ‘Kalabhra’. Could it have been connected to the Tamil word ‘kalvar' for ‘robber’ – or was this word itself derived from old references to the constant raids by these clans living on the borderlands of Tamilakam? Or could ‘Kalabhra’ be the Tamil form of the Sanskrit word ‘kalabha’, which means ‘elephant’, as the area where the Kalabhras originated, from the stretch between Kolar and Chandragiri, was thickly forested elephant country. Others have also connected the Kalabhras to the root word ‘kara’, indicating the colour ‘black’ in Tamil.

One of the most exhaustive studies of this elusive chapter of the South’s history has been done by literary historian M Arunachalam in his work Kalabhras In Pandiya Country & Their Impact On Life & Letters, published by the University of Madras in 1979. A great scholar who studied Tamil literature, Arunachalam decided to delve deeper into this era after he realised that there was a major gap between the rather prolific literary outpouring of the Sangam period, around the 1st BCE-3rd CE and the ‘Age of Hymns’ starting around the 7th CE – a period that saw great devotional poetry by the Nayanars and Alvars, wandering bards who cemented the Shaivite and Vaishnavite resurgence in the South and set the ball rolling for the Bhakti movement that spread far across the subcontinent, all the way till the 16th century.

– Arunachalam astutely observes, “The Kalabhra problem is not merely a political problem but equally a cultural problem.”

The Kalabhras were not just ‘outsiders’, as followers of Jainism, they also represented a different system of beliefs.

Arunachalam makes a case for this hypothesis by pointing out a) that the Sangam Pandyas were followers of the Vedic religion and b) that there was no reference to Jainism or Buddhism in the 2,381-odd verses of Sangam Poetry – which instead has many references to deities such as Shiva, Muruga, Vishnu and Korravai, the Tamil goddess of war and victory.

However, by the end of the 6th CE-7th CE, by when Kalabhra influence would have been evident in the region, according to scholars like Arunachalam, there is a clear indication of a change. We have references to the Royal Pandyas and Pallavas also being Jain.

For instance, the 16-year-old poet, Tiru Jnanasambandar – one of the earliest and most prominent of the 63 Nayanars, i.e. Tamil Shaiva Bhakti saints – is said to have converted the Pandyan king, probably King Arikesari Maravarman, back to Shaivism. Elsewhere in Tondai Nadu, Saint Appar, his contemporary and in fact a senior Nayanar poet, is said to have done the same in the royal house of the Pallavas, where he converted Mahendravarman to Shivaism, also in the 7th CE.

Post-Sangam works like the two epics, the Manimekalai and the Silappatikaram, also have clear Jain leaning and the great Thiruvalluvar, author of the Tirukkural, may have also been influenced by Jainism.

Building on this strong Jain core of the Kalabhras and the period they dominate, Arunachalam goes on to connect them to the area around Shravanabelagola, in Karnataka, the oldest seat of Jainism in the South.

Interestingly, here we find numerous references to ‘Kalikulas’.

In 298 BCE, the founder of the Mauryan Empire Chandragupta Maurya is said to have retreated to the area of present-day Shravanabelagola, marked by two hills Vindhyagiri and Chandragiri (later named after Chandragupta) with a great Jain monk. He went on to perform Sallekhana (or death by starvation in the Jain tradition). Over time, hundreds of Jain shrines cropped up around the site. Later, in 983 CE, the great 57-foot statue of Gommatesvara was built here by Chamundaraya, a Minister in the court of the Ganga dynasty, which ruled the area.

This area of great antiquity and significance to the Jains also holds clues to the Kalabhras. Arunachalam, for instance, points to old Kannada inscriptions in the sites to indicate that the Chandragiri hills were also referred to as Kalvappu or Kallabappu in the inscriptions here, and it is quite likely that the clans of the area were known as Kalabhras.

An old inscription, the earliest in Kannada, from Halmidi in Belur district of Karnataka, not far from Chandragiri hills, mentions the Kalabhras. Here, the Kadamba king Kakusta Varman (425 CE - 450 CE) is said to have been the foe of the ‘Kalabhora’.

Based on all this, Arunachalam paints a rather vivid picture of waves of Kalabhras using the Kaveri and Pennar river waterways to make their way into Tamilakam, whether Kanchi, Kaveripatanam or Madurai, starting around the 3rd CE.

They were probably following a familiar trail taken by Jain monks who had been making their way to Madurai for many centuries before them. Numerous monastic caves with Jain inscriptions have been found around the old Pandyan capital.

The idea that the Kalabhras were more a tribe or clan rather than a single dynasty with a continuum of rulers is iterated by the fact that there is no reference to a royal lineage or chronological listing of the Kalabhras. They left no trace of an administrative system or coins either. Yet they were widely spread – with references to them in Kongunadu, Madurai and in and around Tanjore. This has given credence to the theory that the Kalabhras went down South in waves, to take advantage of the chaos that followed the decline in trade and the gradual weakening of the Sangam-era dynasties around the 3rd CE.

But exactly when they came, how they ruled and how they amalgamated with the locals remains unknown.

Another perspective on the Kalabhras comes from the Gazetteer of Kerala. It points out that while there is no definite literary or epigraphic evidence on the Kalabhras in Kerala, it is presumed that they came in during the closing years of the Sangam Cheras. Here, an interesting inference is drawn from the account of a Nestorian from Alexandria, Cosmos Indicopleustes, who arrived on the Malabar coast around 520-525 CE. It is contended by some scholars that the fact that he didn't mention a Chera or a Chola king or any other chieftain at the helm of affairs indicates the Kalabhras could have been the overlords of the area, in some way.

The Kalabhra Legacy

At the regional centre of the Indian Council of Historical Research in Bengaluru, the Deputy Director, archaeologist Dr S K Aruni, throws further light on the Kalabhra. He believes that the Kalabhras originated most likely in the present-day area of Kalwarbetta, close to the Nandi Hills. A popular trekking site today, there is also an 18th-century fort on this hill.

Dr Aruni points out that his latest surface survey of this region has thrown up evidence of an early historic era site over here.

According to Dr Aruni, it was the Kalabhras who also went on to establish the Early Ganga kingdom. As he points out, “The Gangas also had the elephant as their emblem and early Ganga inscriptions indicate that they were rulers of Anandagiri or Nandagiri, i.e. the Nandi Hills”. Dr Aruni also points out the close association of the early Gangas with the modern-day area of Kolar, associated closely with Kalabhras again. Another strong connect is the fact that the Gangas, like the Kalabhras, were followers of Jainism, and they continued to be for centuries as they expanded their kingdom across Southern Karnataka.

Contrary to the image of the Kalabhras as marauding tribes who left little mark on the rich culture of the South, scholars seem to be arriving at a different view.

According to historian Indira Vishwanathan Peterson, in her work Sramanas Against The Tamil Way - Jains As Others In Tamil Saiva Literature, the Kalabhra period was in no way culturally sterile. She points to the fact that the Kalabhras likely patronised the Sramana religions (Buddhism, Jainism, Ajivikas), more particularly, the Digambara sect of Jainism. Under their patronage, Jain scholars formed an academy in Madurai and wrote texts in Sanskrit, Pali, Prakrit and Tamil. These include classics such as the Tirukkural, the Tamil epics, and many long and short devotional poems. Some of these texts, she points out, "paint a picture of dialogue and mutual tolerance" between the various Indian religions in the Tamil country.

This is not the only legacy of the Kalabhras. Dr Aruni draws our attention to a more direct link to the present. According to him, you can find a connection to the ancient Kalabhras, across the southern tip of Karnataka and the borderlands of Tamil Nadu. He believes that “the Kallar tribe spread from Kolar to Bangarpet, Salem and even Chitoor and are probably modern-day remnants of the Kalabhra clans”.

Sadly, more than a century after the discovery of the Velvikudi Grants, and numerous attempts by scholars to trace their trail, the Kalabhras continue to be elusive. While they seem to have been a wave that passed and settled in wisps across the sands of South India’s history, perhaps the best way to look at them is from further afield – the stretch down the holy Chandragiri, where the Gangas left their most lasting mark on faith and history.

This article is part of our 'The History of India’ series, where we focus on bringing alive the many interesting events, ideas, people and pivots that shaped us and the Indian subcontinent. Dipping into a vast array of material - archaeological data, historical research and contemporary literary records, we seek to understand the many layers that make us.

This series is brought to you with the support of Mr K K Nohria, former Chairman of Crompton Greaves, who shares our passion for history and joins us on our quest to understand India and how the subcontinent evolved, in the context of a changing world.