Goa Revolution Day: A Forgotten Story

BOOKMARK

In the heart of Panaji in Goa is a street with a mysterious name – it simply reads ‘18th June Road’.

But behind the kitsch and other wares being sold to unsuspecting tourists in this shoppers’ haven is the story of one of the most defining events in Goa’s modern history. June 18, 1946, is Goa Revolution Day, the day Goans seized their destiny and vowed to take back their homeland from the Portuguese.

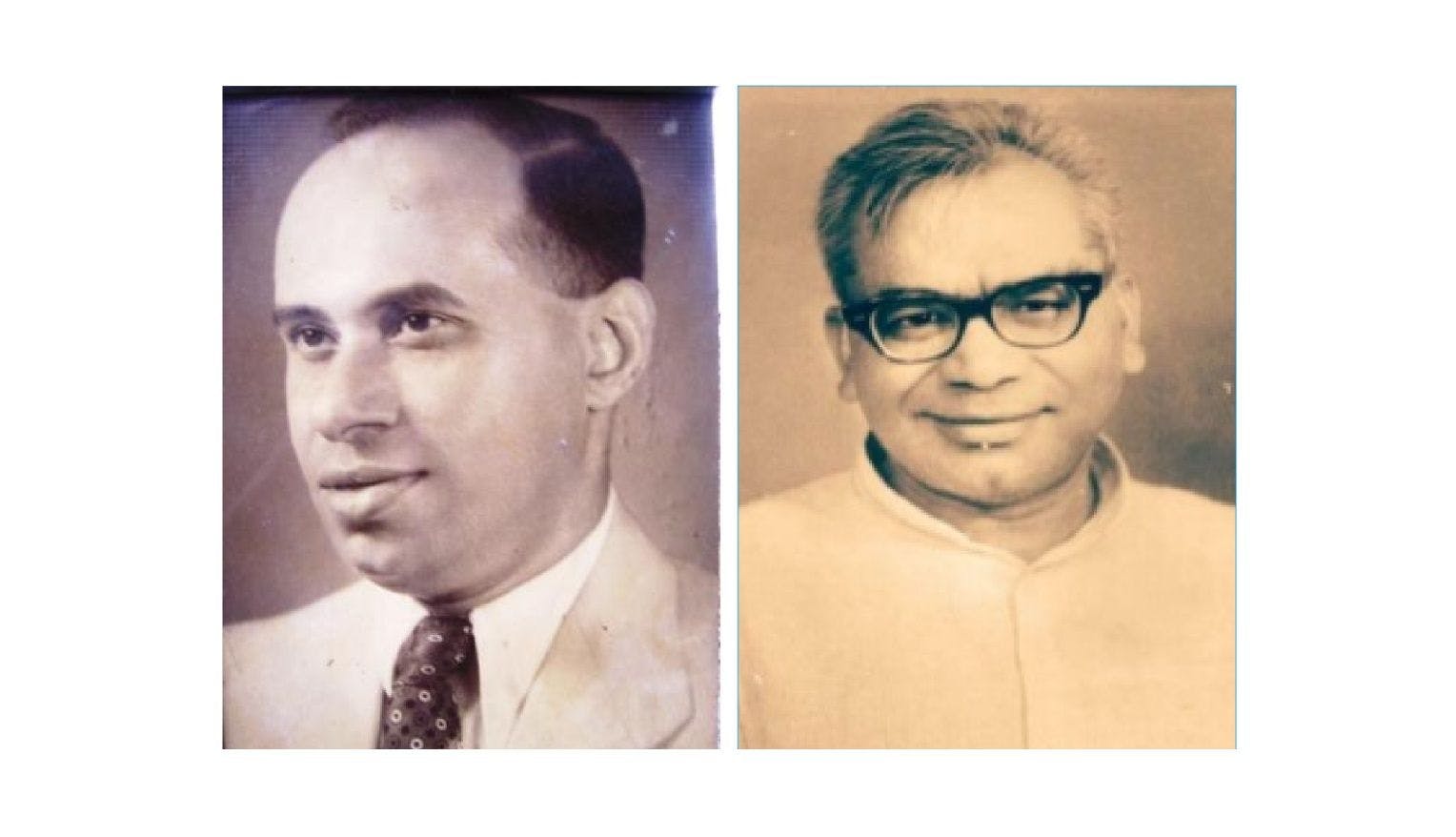

In 1946, Goa was still 15 years from being liberated but the seeds of freedom were sown in a friendship forged between two young students in the University of Berlin in the late 1920s. One was a boy from Goa and the other was a lad from Akbarpur in present-day Uttar Pradesh. They were Juliao Menezes and Ram Manohar Lohia.

Both Menezes and Lohia were driven by a nationalist zeal and bonded instantly over their shared dream. While Lohia acquired a PhD and returned to India in 1933, Menezes completed his MD and returned to Goa in 1938. Menezes then moved to Bombay, from where he campaigned for Goa’s civil liberties. He had stayed in touch with Lohia all those years and, in Bombay, even offered Lohia refuge when he went underground during the Quit India Movement.

– While India calls the Annexation of Goa by the Indian armed forces in 1961 the ‘Liberation of Goa’, the Portuguese call it the ‘Invasion of Goa’.

When Lohia took ill in 1946, Menezes suggested that he convalesce in his home in his village Assolna in South Goa. Lohia accepted the invitation but resting was out of the question. Almost as soon as he got there, on 10th June 1946, a stream of intellectuals and political activists started arriving to discuss Goa's freedom struggle.

And, just like that, in the Menezes home, the movement for Goa’s civil liberties was born.

On 15th June, Menezes and Lohia addressed a public meeting in Panaji. It was an act of civil disobedience as public meetings had been banned by the Portuguese government. But the men were not stopped and, emboldened by their success, they arranged another public rally. This was to be held in Margao on 18th June.

On the appointed date, a massive crowd assembled in the Margao square and they greeted Menezes and Lohia loudly as they drew up in a horse carriage. It was an ingenious way to get around the ban on cars entering the town.

Addressing the people, Menezes and Lohia gave a clarion call to shake off colonial rule and take back what was rightfully theirs. They called for revolution.

– The Portuguese administration did not read the writing on the wall and called the Civil Disobedience Movement a ‘movimento da rua’ or a ‘roadside agitation’.

The Portuguese government was caught completely off-guard. They had not expected such a humongous turnout, and they had not expected such an outpouring from their ‘subjects’.

Menezes and Lohia were arrested and, under the cover of darkness, whisked away to the Panaji police station.

The colonial administration couldn’t have anticipated what happened next. The next day, as news of the arrests spread, Goans took out processions in the streets, in cities and in towns across the state. Refusing to back down, they stubbornly squatted on the roads, chanting slogans such as: “Jai Hind! Dr Lohia ko chhod do! Dr Juliao Menezes ko chhod do!

Lohia was escorted to the Goa border and released there, while Menezes was let off in Margao.

But the fatal blow had been struck – these two freedom fighters had ushered in a revolution that eventually got Goa her freedom from the Portuguese.