The Year Madras Froze

BOOKMARK

About 200 summers ago, there was a winter not of discontent, but of surprise.

Why? Well, because it defied all logic. It happened in hot and humid Chennai!

Bizarre as it may sound to anyone, especially those who have been to the southern Indian city, this freak chill came down on Madras, as Chennai was known then, one week in April, 1815.

While the thermometer showed an already uncharacteristic 11 degrees Celsius on Monday, April 24, it is said to have plummeted to minus 3 degrees Celsius, four days later on April 28. Some say there was snowfall, but that has never been proven.

So what really happened?

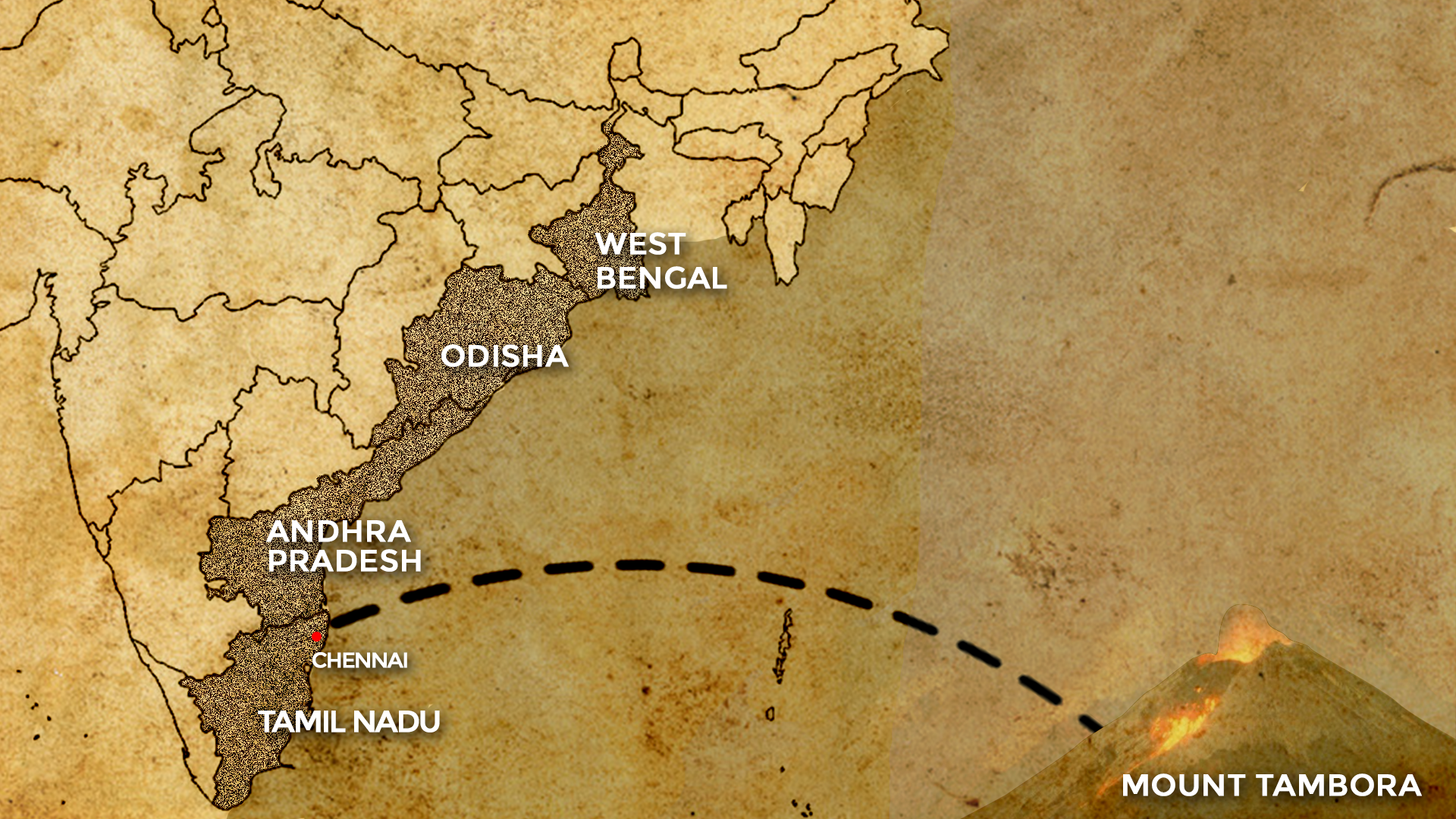

In 1815, ‘Mother Nature’ was thrown out of step, due to the biggest recorded volcanic eruption in history, when Mount Tambora, jutting out of the island of Sumbawa, just off the coast of Indonesia, thundered into the atmosphere.

Dormant for about 1000 years before, on April 10 and 11, 1815, the 9,350 ft mountain spewed out lava with such ferocious expression, that the explosion itself killed around 12,000 people and was heard 2,000 km away.

That was just the teaser.

In ‘Tambora: The Eruption That Changed The World,’ Gillen D’Arcy Wood eloquently describes what happened, ‘Tambora’s dust veil, serene and massive above the clouds, began its westward drift aloft the winds of the upper atmosphere. Its airy passage to India outran the thousands of waterborne vessels below bent upon an identical course, breasting the trade winds from the resource-rich East Indies to the commercial ports of the Indian Ocean. The vanguard of Tambora’s stratospheric plume arrived over the Bay of Bengal within days.’

– Tambora’s eruption caused havoc across the world with temperatures dipping by as much as 1.5 degrees Celsius

It arrived and how ! Madras was one of the first to feel the after-effects of Tambora's fury. It was so drastic that the entire Indian subcontinent reeled under it. Apart from the freezing temperatures, the eruption caused an ash plume that was released 33 km into the air, roughly 3-4 times higher than your average Bombay-Delhi flight!

Almost 55 million tons of sulphur dioxide spread into the stratosphere and formed vast aerosol clouds that circumnavigated the Earth in two weeks and blocked out the sun, causing the temperatures to dip across the globe.

A ‘dry fog’ of aerosols was observed in the northeastern United States, such that sunspots were visible to the naked eye. Frost was reported in the upper elevations of New Hampshire, Maine, Vermont and northern New York. Canada was buried in 12 inches of snow at some places like Quebec City.

– The volcanic ash and aerosol clouds blocked out the sun, making that year the second coldest ever in the Northern Hemisphere

In the summer of 1816, countries in the Northern Hemisphere, all suffered extreme weather conditions, including unusually-colored sunsets. Average global temperatures dipped by 0.4–0.7 °C, causing significant agricultural problems. Conditions persisted for at least three months and ruined most agricultural crops in North America. 1816 became the second-coldest year in the Northern Hemisphere since around 1400.

The spreading ash cloud made the 1816, the ‘year without summer’ for much of the world. In Madras, and the rest of India, it also meant a year without the monsoons. Failed crops and famine ravaged the country and led to a widespread outbreak of cholera with Bengal being affected in particular.

Tambora killed 70,000 people globally in its aftermath.

Apart from a cooler summer, parts of Europe experienced a stormier winter. This climactic change brought with it a severe typhus epidemic in southeast Europe and the eastern Mediterranean between that lasted three years.

– Tambora’s eruption caused famine and disease in which around 70,000 people died

Cool temperatures along with intermittent heavy rains resulted in failed harvests in Britain and Ireland, Wales saw a lot of displacement. People travelled long distances as refugees, following the failure of wheat, oat, and potato harvests.

It was the worst famine of the 19th century in the West.

The East India Company records however chose to be conservative about this destructive event. The colonial masters had muted reactions to the occurrence, perhaps a cover-up for their lack of preparedness to handle the consequences.

But one does hear that the Madras coastline was awash with pumice rock for years, the one reminder of the devastation that was wreaked on the people in the city and elsewhere across the world.