‘Kolkata Ek’: Where It All Began

BOOKMARK

Dalhousie Square, or ‘BBD Bag’ as it is popularly known, is still considered by many to be the heart of Kolkata. While the state Secretariat may have shifted from the venerable Writers’ Building to the swanky new Nabanna across the Hooghly River in October 2013, BBD Bag (named after freedom fighters Benoy Bose, Badal Gupta and Dinesh Gupta) remains ‘Office Para’, from where the majority of government and a multitude of business houses still operate. The pin code of the neighbourhood is still a proud 700001 or ‘Kolkata Ek’, as Bengalis say.

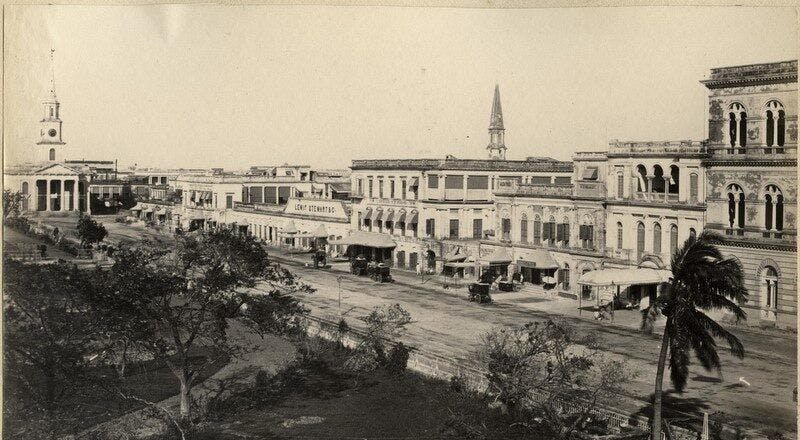

But what the multitudes who flock to Office Para every day (or used to, before the pandemic), have forgotten is that this is where the modern city of Kolkata began. Sure, Govindpore, Sutanuti and Kolikata were already established villages, but they were little more than hamlets. Sutanuti did have a thriving textile market, from which it got its name. But the city of Kolkata that we see today has its origins in the British East India Company’s settlement, and that began, right here, at Office Para.

The early records of the Company show that Job Charnock landed in 1690 CE near the place that is now the Nimtala Cremation Ghat. After his death in 1693 CE, the Company appointed Sir John Goldsborough to take over the factory, which was then located in the village of Sutanuti, which corresponds to today’s North Kolkata.

It was Goldsborough who identified a spot between the Hooghly River to the west and the large tank known as Lal Dighi on the east as the site of the future factory. The spot was higher than the surrounding ground, which made it immune to being inundated during the monsoons.

This spot, on which the GPO, the Calcutta Collectorate, the Reserve Bank of India headquarters and the Fairley Place headquarters of the Eastern Railway stand today, became the spot where Kolkata’s first Fort William was constructed between 1696 CE and 1717 CE. The fort became the centre of the European settlement in the area, with houses of merchants being built all around it. St Anne’s Church was built to the east of the fort and consecrated in 1709 CE. The cemetery for the Europeans was some distance away, to the south of the church.

But less than 40 years after it was built, Fort William was destroyed in a devastating battle. The Company had severely underestimated the new Nawab of Bengal, Siraj-ud-Daula, who attacked the settlement with an army of 50,000. After a siege that lasted three days, the English were defeated and expelled from their settlement. However, less than a year later, with help from forces from Madras led by Robert Clive and Vice Admiral Charles Watson, the East India Company would retake Calcutta and eventually unseat Siraj-ud-Daula in the Battle of Plassey in 1757.

Dalhousie Square had been thoroughly devastated in the siege. A part of the fort had been torn down for the construction of a mosque, St Anne’s had been blown to smithereens by cannon fire and the merchants’ houses were in a shambles.

Learning from their mistakes, the East India Company chose to relocate Fort William, further south. This was the village of Govindpore, which was vacated, creating a large swathe of open ground. The new Fort William was built here, giving it a good field of fire on the east and the protection of the Hooghly River on the west.

Still A Trading Hub

The importance of Dalhousie Square as a trading centre did not diminish even though the fort had shifted. With the establishment of the original factory, the ghats to the west of the square had become the principal port of the city and this would continue until the construction of the Kidderpore Docks was completed in 1870.

Thanks to the trade in the area, Bankshall or Marine House, which housed the offices of the port’s manager, was located in Dalhousie. While Bankshall does not exist any longer, the court that has taken its place is known as ‘Bankshall Court’. Kolkata’s Customs House was located in Dalhousie Square as well, and although the old building was demolished, the Customs House relocated to a spot not far from Dalhousie, and continues to operate out of that area.

– Because the ghats were used as a trading port, the lanes around Dalhousie Square became infamous for their drinking dens.

Among the many taverns, the most famous was Harmonic Tavern, which stood where the Lalbazar Police Headquarters stands today. Among the many delicacies served at Harmonic Tavern was oysters. The tavern even had a well to keep them fresh!

On 6th September 1833, a sensation was caused by the arrival of the American vessel Tuscany, which contained an item that the labourers unloading ships had never seen before – ice! The ice trade between Boston in America and Calcutta in India was extremely profitable and the city’s only ice house was constructed adjacent to Dalhousie Square. It was demolished in 1882 as the advent of steam-powered ice-making machines had made it obsolete.

Along with the ice house, a number of other things have also disappeared over time. With the Hooghly River retreating towards Howrah by 100 metres in the last two centuries, many of the ghats of the old Dalhousie Square, such as Brightman’s Ghat, have been altogether forgotten and built over. Several other ghats, such as the monumental Prinsep Ghat, have been left stranded far from the river bank.

However, even with the removal of the port to Kidderpore, the importance of Dalhousie Square as a centre of trade did not diminish. Perhaps due to the remote location of the new port, or perhaps because human traffic mostly remained concentrated around Dalhousie Square, business houses continued to operate from the area.

The Viceroy Moves In

Kolkata’s Raj Bhavan, once home to the British Viceroy, was completed in 1803 and was located to the south of Dalhousie Square. Through the latter half of the 19th century, the colonial government would continue a drive to aggressively acquire as many properties as possible in and around the Viceroy’s residence, to relocate government departments in close proximity.

Writers’ Building, constructed in 1777 CE as residences for the East India Company’s clerks, was converted into the Bengal Secretariat in 1877. By 1882, Spence’s, Asia’s first hotel, had moved and its place, to the south of Dalhousie Square and to the west of Raj Bhavan, had been taken by the Treasury Building, which housed more government departments. By 1892, the Collectorate Building had been built across the street from Writers’.

These monolithic office blocks set the tone for government architecture in colonial Calcutta and contain many elements in common – the arched windows, the mansard roof, and the exposed brick and stucco exterior, which is now painted red and yellow. Greco-Roman inspired figurines were commonly used as decorations on these buildings and most survive in good shape even today.

Dalhousie’s Architectural Puzzle

The other major part of the architectural puzzle of Dalhousie Square are its managing agency houses. Explaining what exactly a managing agency is and how it functioned is well beyond the scope of this article. Suffice it to say that it is a system of doing business that has long since been outlawed in India, but was commonplace in the colonial era. While the agencies themselves were small and operated with limited staff, they built magnificent offices in the Dalhousie area, which were rented to the hundreds of firms who operated in the area.

The managing agency houses of Dalhousie Square present a fascinating and bewildering variety of architectural styles. There is the stone-clad Hong Kong House, which still houses HSBC Bank. The red and white stripes of the Chartered Bank building were created using exposed brick and Chunar stone. Stucco ornamentation was also popular, and two insurance buildings, Standard Life Assurance and the Oriental Assurance building contain some of the most beautiful stucco decorations in all of Kolkata.

A surprisingly large number of them were built by Martin & Co, which also built Kolkata’s most prominent landmark – the Victoria Memorial. Many buildings employed some of the biggest names in architecture of the time, such as William Banks Gwyther and Harry Stuart Goodhart-Rendel. The latter was the maverick behind the design of the colossal headquarters of Gillanders Arbuthnot & Co. The building, with its semi-circular façade, has such a mix of architectural styles that it is almost impossible to pigeonhole.

The majority of these managing agencies were Scottish-owned, and the concentration of so many of them in one small neighbourhood led to certain other things. For example, the only Scottish church or ‘kirk’ in all of Kolkata, St Andrew’s, still stands at the north-eastern corner of BBD Bag. St Andrew’s Day dinners were also a rather gala affair in colonial Calcutta, a tradition sadly discontinued.

Hindi movie film star Amitabh Bachchan started his career as an employee of one such former managing agency – Bird & Co. It is perhaps difficult to imagine that one of the biggest film stars of India was once paid a salary of Rs 500 a month, which was reduced to Rs 460 after statutory deductions for gratuity and provident fund.

In Kolkata for the shooting of the film Piku in 2014, a nostalgic Bachchan had detailed how he had struggled to survive on this meagre salary – “350 rupees a month gone for bed and lodging, food separate, eating the pani puri or the puchka pani at Victoria Memorial. 2 rupees would fill the stomach. That’s it, and done for the entire day... looking forward to the free office lunch the next morning!"

But, of course, no discussion on Kolkata’s Office Para is complete without at least a mention of Dacres Lane. The street gets its name from Phillip Milner Dacres, who arrived in Kolkata from England in 1756 CE and was appointed Assistant Import Warehouse-Keeper. He would go on to become Collector of Calcutta in 1773 CE and ultimately returned to England in 1784 CE. The street is now named after James Augustus Hicky, the Irishman who launched the first printed newspaper in India, Hicky’s Bengal Gazette.

But while the nomenclature of the street is interesting, what it is famous for is its food. Every afternoon, thousands of hungry office-goers descend on Dacres Lane to eat their fill for a price that perhaps would be unthinkable elsewhere. While there are many shops serving everything, from chowmein to poori-sabzi, the one shop that has achieved near-mythical status is known simply as ‘Chitto Babu-r Dokan’ (Chitto Babu’s Shop), which is famous for its stew and toast.

For those looking for something crunchier, there is also the famous fish fry from Chitto Babu’s restaurant, Suruchi. Succulent, juicy filets of fish, marinated to perfection, rolled in bread crumb and then fried to a golden brown, it would be hard to find a Bengali foodie who has not heard of Chitto Babu.

Many residents of the more modern South Kolkata, who do not work in the Dalhousie area, will recall early morning taxi rides through Dalhousie Square on their way to board a train at Howrah station. For those more used to the modern architecture of South Kolkata, once the Maidan has been crossed, it is like entering a different world. In the rest of the city, one has to go looking for heritage buildings. In Dalhousie Square, practically every single building is a protected heritage structure.

Recent efforts from both the government and private organisations have led to the renovation of several of these architectural gems. But many more remain neglected and decaying. Every building in the neighbourhood has a story to tell. It is perhaps the strongest contender for Kolkata’s first heritage district.

Now, get a chance to engage with leading experts from across the world, enjoy exclusive in-depth content, curated programs on culture, art, heritage and join us on special tours, through our premium service, LHI Circle. Subscribe here.